A few words and reflections over the Christian messiah, and how to deal with a religious heritage when moving to another one.

Quelques mots et réflexions sur le messie du Christianisme, et comment gérer un héritage religieux dans un chemin de conversion.

My background : Protestantism

My personal religious background is Protestantism. I was baptised as a young child, and I got a few religious courses at the local protestant church in my hometown. My relationship with Jesus was difficult and complex. When I was a child, my parents offered me a small comic dedicated to the New Testament, with a few pages discussing major themes of the Old Testament : the Flood, Noah’s Ark, Babylonian invasion… Unfortunately and unbeknownst to my parents : I was captivated by these first pages of the comics, and I was unwilling to read the next sections. Growing older, I became proud of my Protestant heritage but solely for intellectual reasons : search for simplicity, disdain for dogma, constant willingness to interrogate and debate everything…

Mon parcours religieux personnel est protestant. J’ai été baptisé quand j’étais enfant et j’ai suivi quelques cours de religion à l’église protestante locale de ma ville natale. Ma relation avec Jésus a été difficile et complexe. Quand j’étais enfant, mes parents m’ont offert une petite bande dessinée consacrée au Nouveau Testament, avec quelques pages traitant des thèmes majeurs de l’Ancien Testament : le Déluge, l’Arche de Noé, l’invasion babylonienne… Malheureusement, à l’insu de mes parents, j’ai été captivé par ces premières pages de la bande dessinée et je n’ai pas voulu lire les sections suivantes. En vieillissant, je suis devenu fier de mon héritage protestant, mais uniquement pour des raisons intellectuelles : recherche de la simplicité, mépris du dogmatisme, volonté constante de tout remettre en question et de tout débattre…

From non-practicing Protestant to Judaism enthusiast

To be transparent, I was never religious for a long time, until my early 30s. I did believe at times in Jesus — but it was limited and intellectual. My relationship with Jesus was challenged when I discovered Judaism in my early 30s. At 28–29 years old : I decided to read for the first time the Bible, both the Old and New Testament. I got a precious book : the NBS (“Nouvelle Bible Segond — Edition d’étude”, or in English “New Segond Study Bible”). This Bible edition is extremely interesting because every single book is introduced by historical and archeological notes. I was quickly fascinated by the complex history of the Old Testament, the destiny of the Hebrew people and all the events described in vivid details : battles, flooding, love stories, exodus… Reading and questioning the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible was my key motivation to study Judaism, and sent my letter to the French Consistoire in Paris.

Pour être honnête, je n’ai jamais été très croyant jusqu’à l’âge de 30 ans. Je croyais parfois en Jésus, mais de manière limitée et intellectuelle. Ma relation avec Jésus a été remise en question lorsque j’ai découvert le Judaïsme au début de la trentaine. À 28–29 ans, j’ai décidé de lire pour la première fois la Bible, l’Ancien et le Nouveau Testament. Je me suis procuré un livre précieux : la NBS (« Nouvelle Bible Segond — Édition d’étude »). Cette édition de la Bible est extrêmement intéressante, car chaque livre est introduit par des notes historiques et archéologiques. J’ai rapidement été fasciné par l’histoire complexe de l’Ancien Testament, le destin du peuple hébreu et tous les événements décrits avec force détails : batailles, inondations, histoires d’amour, exode… La lecture et l’étude de l’Ancien Testament ou de la Bible hébraïque ont été ma principale motivation pour étudier le Judaïsme et envoyer ma lettre au Consistoire français à Paris.

The rediscovery of Jesus

I read the New Testament too, but the story was less appealing to me. But one man captivated my attention : Jesus. My choice to shift to Judaism interrogated me over this figure : what should I do over him ? My deep studies of the Hebrew Bible led me to the conclusion that Jesus couldn’t be the Son of God. The Judaic theology is clear : God is infinite, God cannot be divided nor God could be impersonated by a human figure. But the figure became intriguing. I read several books about him : Christian ones and theological ones. One day, I decided to buy the most important movie about Jesus — considered a hallmark on the topic : Jesus of Nazareth by Franco Zeffirelli made in 1977 for the television. It’s probably the most complete and respectful account of Jesus’ life based on the Gospels from the New Testament (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John).

J’ai lu le Nouveau Testament aussi, mais l’histoire m’a moins plu. Mais un homme a captivé mon attention : Jésus. Mon choix de me convertir au Judaïsme m’a amené à m’interroger sur ce personnage : que devais-je faire à son sujet ? Mes études approfondies de la Bible hébraïque m’ont conduit à la conclusion que Jésus ne pouvait pas être le Fils de Dieu. La théologie juive est claire : Dieu est infini, Dieu ne peut être divisé, et Dieu ne peut être incarné par un être humain. Mais ce personnage est devenu intrigant. J’ai lu plusieurs livres à son sujet : des livres chrétiens et des livres théologiques. Un jour, j’ai décidé d’acheter le film le plus important sur Jésus, considéré comme une référence sur le sujet : Jésus de Nazareth, réalisé par Franco Zeffirelli en 1977 pour la télévision. C’est probablement le récit le plus complet et le plus respectueux de la vie de Jésus, basé sur les Évangiles du Nouveau Testament (Matthieu, Marc, Luc et Jean).

Zeffirelli’s “Jesus of Nazareth” and Jesus importance to me

The performance of Edward Powell — Jesus actor — is astonishing. The best scene from the movie ? The Temple scene — Matthew chapters 21 to 23 for the most complete version, Luke chapter 20 and Mark chapters 11 to 12. This moment in Zeffirelli’s movie was so crucial for me that it led me to interrogate myself over my path to Judaism. In the Temple scene, one sentence struck me as an inner truth:

“If you were blind, you would have no sin, but since you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains.”

I heard it as a warning: the danger does not come from ignorance, but from certainty. It is not doubt that distances us from God, but the pride of believing that we already know. These words resonate within me as a call to remain humble, curious, and sincere in my quest for truth. Was I missing something in Christianity ? While studying the Hebrew Bible and reflecting on Jewish customs — not eating pork or mixing dairy/meat, Shabbat… — the movie interrogated once again my relationship with Jesus. Put aside the New Testament, no other sources mention Jesus and its ministry. While a strictly personal opinion : I did believe that someone in the past, in Judea, has done or said things that left a deep impact on his contemporaries. No other explanation, from my perspective, could explain such an enthusiasm in early Christian communities. My willingness to embrace Judaism was more intellectual and theological than spiritual. The goal was not to condemn Christianity. I had to find a way to reconcile myself with this small christian heritage and embrace Judaism.

La performance d’Edward Powell, l’acteur qui incarne Jésus, est époustouflante. La meilleure scène du film ? La scène du Temple, dont on trouve la version la plus complète dans Matthieu, chapitres 21 à 23, Luc, chapitre 20, et Marc, chapitres 11 à 12. Ce moment du film de Zeffirelli a été si déterminant pour moi qu’il m’a amené à m’interroger sur mon cheminement vers le Judaïsme. Dans la scène du Temple, une phrase m’a frappé comme une vérité intérieure :

“Si vous étiez aveugles, vous seriez sans péché, mais puisque vous dites : « Nous voyons », votre péché demeure.”

J’y ai entendu un avertissement : le danger ne vient pas de l’ignorance, mais de la certitude. Ce n’est pas le doute qui éloigne de Dieu, c’est l’orgueil de croire qu’on sait déjà. Cette parole résonne en moi comme un appel à rester humble, curieux, et sincère dans ma quête de vérité. Est-ce que quelque chose me manquait dans le Christianisme ? Tout en étudiant la Bible hébraïque et en réfléchissant aux coutumes juives — ne pas manger de porc ou mélanger les produits laitiers et la viande, le Shabbat… — , le film m’a amené à remettre en question ma relation avec Jésus. Mis à part le Nouveau Testament, aucune autre source ne mentionne Jésus et son ministère. Bien qu’il s’agisse d’une opinion strictement personnelle, je crois sincèrement qu’une personne, dans le passé, en Judée, a fait ou dit des choses qui ont eu un impact considérable sur ses contemporains. À mon sens, aucune autre explication ne pourrait justifier un tel enthousiasme dans les premières communautés chrétiennes. Ma volonté d’embrasser le Judaïsme était plus intellectuelle et théologique que spirituelle. Le but n’était pas de condamner le Christianisme. Je devais trouver un moyen de me réconcilier avec ce petit héritage chrétien et embrasser le Judaïsme.

Keeping a fragment

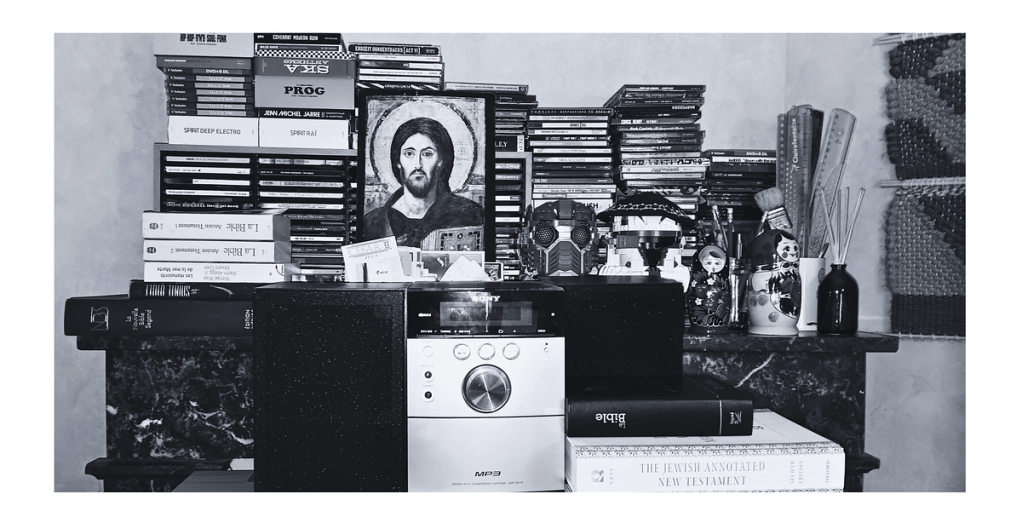

I watched Gad Elmaleh movie “Reste un peu”. It’s a semi-autobiographical movie : Gad plays his own role describing his path from Judaism to Christianity. The main theme of the movie is how to keep a religious heritage while moving to another one. My solution was to keep something in my most personal space : my own room. It came in the form of an old icon : a reproduction of the Christ Pantocrator (Sinai icon) — something I got in the small shop near my local church. Something comical given my religious way of thinking. I came and moved from two religious traditions which refuse icons : Protestantism and Christianity. But it was the best idea from my perspective : keeping a material fragment of this christian background — like a memory of the past. Something that has nothing to do with faith.

J’ai regardé le film « Reste un peu » de Gad Elmaleh. C’est un film semi-autobiographique : Gad joue son propre rôle et décrit son parcours du Judaïsme au Christianisme. Le thème principal du film est comment conserver son héritage religieux tout en adoptant une autre religion. Ma solution a été de conserver quelque chose dans mon espace le plus personnel : ma propre chambre. Cela a pris la forme d’une vieille icône : une reproduction du Christ Pantocrator (Sinaï) — que j’ai achetée dans une petite boutique près de mon église locale. Quelque chose de comique compte tenu de ma façon de penser religieuse. Je suis issu de deux traditions religieuses qui refusent les icônes : le protestantisme et le Christianisme. Mais c’était la meilleure idée selon moi : conserver un fragment matériel de ce passé chrétien, comme un souvenir du passé. Quelque chose qui n’a rien à voir avec la foi.

Conclusions

In my goal to understand and integrate Judaism, I opened a website dedicated to the Hebrew Bible — from an historical, archeological, cultural and theological perspective; something absolutely not proselytic. I wrote an important article for named “Une lecture comparative de la Bible Hébraïque, entre Judaisme et Christianisme” (“A comparative reading of the Hebrew Bible, between Judaism and Christianity”) — the opportunity to discuss how both traditions read the Hebrew Bible, and what occurred for both religious groups to split. To quote my paper’s own conclusion :

“If we were to summarize the two approaches, we could first note that in Judaism, the Hebrew Bible (and more specifically the Torah or Pentateuch) is a central text in religious practice, and that nothing can abrogate or replace it. In Christianity, on the other hand, the term Old Testament refers to a complement that is the New Testament. Secondly, despite the fact that Abraham is a common ancestor of both religions, there are differences in how this fact is interpreted today. The covenant between Abraham and God is still relevant in Judaism and is manifested in the rite of circumcision, whereas in Christianity this rite has been spiritualized. As for the question of recognizing one God, the two religions agree, but certain practices can lead to disagreements on both sides: for example, the Christian Trinity, which is difficult for Judaism to understand. The question of the Messiah is also important: Judaism is still waiting for its Messiah, while Christianity recognizes him in the person of Jesus. We also saw the differences in interpretation between Christianity and Judaism on subjects such as human nature, studying in particular how the fall of Adam is interpreted.” — While written with the best neutrality, I do believe that’s the key reason I decided to move from Protestantism to Judaism.

Dans le but de comprendre et d’intégrer le Judaïsme, j’ai créé un site web consacré à la Bible hébraïque, d’un point de vue historique, archéologique, culturel et théologique, sans aucune intention prosélyte. J’ai rédigé un article important intitulé « Une lecture comparative de la Bible hébraïque, entre Judaïsme et Christianisme », qui m’a donné l’occasion d’examiner comment les deux traditions interprètent la Bible hébraïque et ce qui a conduit à la scission entre les deux groupes religieux. Pour citer la conclusion de mon article :

“Si on devait faire une synthèse des deux approches, on pourrait d’abord retenir du Judaïsme que la Bible Hébraïque (et plus particulièrement la Torah ou Pentateuque) est un texte central dans la pratique religieuse, et que rien ne vient l’abroger ou le remplacer. Au contraire, dans le Christianisme, le terme d’Ancien Testament appelle un complément qui est le Nouveau Testament. Ensuite, malgré le fait qu’Abraham soit un ancêtre commun aux deux religions, il y a des divergences quant au sens à donner aujourd’hui à ce fait. L’alliance entre Abraham et Dieu est toujours d’actualité dans le Judaïsme et se manifeste par le rite de la circoncision, quand dans le Christianisme ce rite a été spiritualisé. Quant à la question de la reconnaissance d’un Dieu unique, les deux religions s’accordent, mais certaines pratiques peuvent entraîner des désaccords de part et d’autre : par exemple la Trinité chrétienne qui est difficilement compréhensible pour le Judaïsme. La question du Messie est également importante : le Judaïsme attend toujours le sien quand le Christianisme le reconnaît en la personne de Jésus. Nous avons également pu voir les différences d’interprétations entre Christianisme et Judaïsme sur des sujets comme la nature humaine, en étudiant notamment la façon dont la chute d’Adam est interprétée.” — Bien que rédigé avec la plus grande neutralité possible, je pense que ce sont là les principales raisons qui m’ont poussé à passer du protestantisme au Judaïsme.

Two words for Jesus

Jesus, it would be dishonest to say that I believed in you when I was younger — in the religious sense of the term. But to be honest with you, rediscovering your character through Zeffirelli’s film opened my eyes to a hypothesis: you weren’t the Son of God — that’s impossible according to Judaism — but you must have been a good, generous, and open man who touched the men and women of your time in Judea with your words and hands. The mere existence of Christianity is proof enough of that. You still intrigue me today. And to quote yourself directly from the Scriptures: “But who do you say that I am?” — I don’t know, but that’s enough to keep my curiosity and your mystery alive.

Jésus, ce serait malhonnête de dire que j’ai cru en toi plus jeune — au sens religieux du terme. Mais pour être honnête avec toi, la redécouverte de ton personnage avec le film de Zeffirelli m’a ouvert les yeux sur une hypothèse : tu n’étais pas le Fils de Dieu — c’est impossible d’après le Judaïsme — mais tu devais être un homme bon, généreux et ouvert qui a su toucher de ses mots et mains les Hommes et Femmes de ton temps en Judée. La simple existence du Christianisme suffit à le prouver. Tu m’intrigues encore aujourd’hui. Et pour te citer d’après les Ecritures : “Et vous, qui dites-vous que je suis ?” — je n’en sais rien, mais ça suffit à entretenir ma curiosité et ton mystère.

Laisser un commentaire