Last week, I watched a Youtube video about a relatively unknown East German political figure : Günter Schabowski. Born in 1929, and deceased in 2015, he was largely unknown outside East Germany; despite having climbed the ladder in the Socialist Unity Party of Germany and being at this time an unofficial spokesman of the government. On 9 November 1989 — the day of the Berlin Wall fall — he was tasked to answer journalist questions. Before the press conference, he was handed a note regarding the new regulation to allow East Germans to travel outside the country.

What was a simple note leads to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Günter Schabowski discussed the note openly during the press conference. Because he was not clearly informed on this new regulation, he states that the border was immediately opened. The press conference was live-broadcasted in East and West Germany, creating growing crowds at the Berlin Wall on both sides. Without guidance and orders, the border guards had no other option than letting people go through. It was the end of the 28-year life of the “Iron Curtain”.

The fact is that, unfortunately for the Berlin Wall and East Germany, their fate was sealed well before Günter Schabowski answered questions at his press conference on 9 November 1989. As a reminder, East Germany (or German Democratic Republic) was born in 1949 after World War II and the takeover by the Soviet Union over Eastern Europe. The country was forced to pay war reparations for some times, but ultimately became the most successful country of Eastern Europe.

The main difficulties for East Germany were a growing exodus starting in the early 1950s to West Germany. It’s worth noting that the Soviet authorities faced an uprising in 1953 in East Germany. In the meantime, authorities started to create the “inner border” system, in order to progressively cut Eastern Europe from Western influences. But it was not enough, especially because people crossed the border at Berlin. The decision was finally taken to build the wall on 13 August 1961, during an event that was called the “ Barbed Wire Sunday”.

What could have been the creation of a simple “walled” border was probably far more important than that. It could described by this simple formula :

East Germany = Berlin Wall

Many countries in the world have (or had) tightly controlled borders : United States wall with Mexico, North/South Korea demarcation line… The East Germany case is special : it’s a divide between the same people. A divide that was totally artificial. East Germany had far more complex borders across the country, but the Berlin Wall was extremely symbolic : it was a divide within a city inhabited by the same people (set apart their political stances). And when something as symbolic as that is done, it becomes the sole thing people see years after years. Something extremely ugly (a quickly built brick wall) and extremely shameful too (the unnatural divide within a city and between a people). Whatever could have been the success of East Germany, for people outside and inside, the country was the Berlin Wall. Nothing more nothing less. The Berlin Wall, in some way, became part of the East German leadership psyche. Erich Honecker (1912–1994), last General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party, was extremely invested in the Berlin Wall security. He was one of the people responsible for its construction.

The economic “honeymoon” of East Germany — especially in electronics and consumer products — was relatively short lived, as many other countries of Eastern Europe faced growing economic issues beginning in early 1980s. The economic success was extremely dependent on regular borrowing from West Germany.

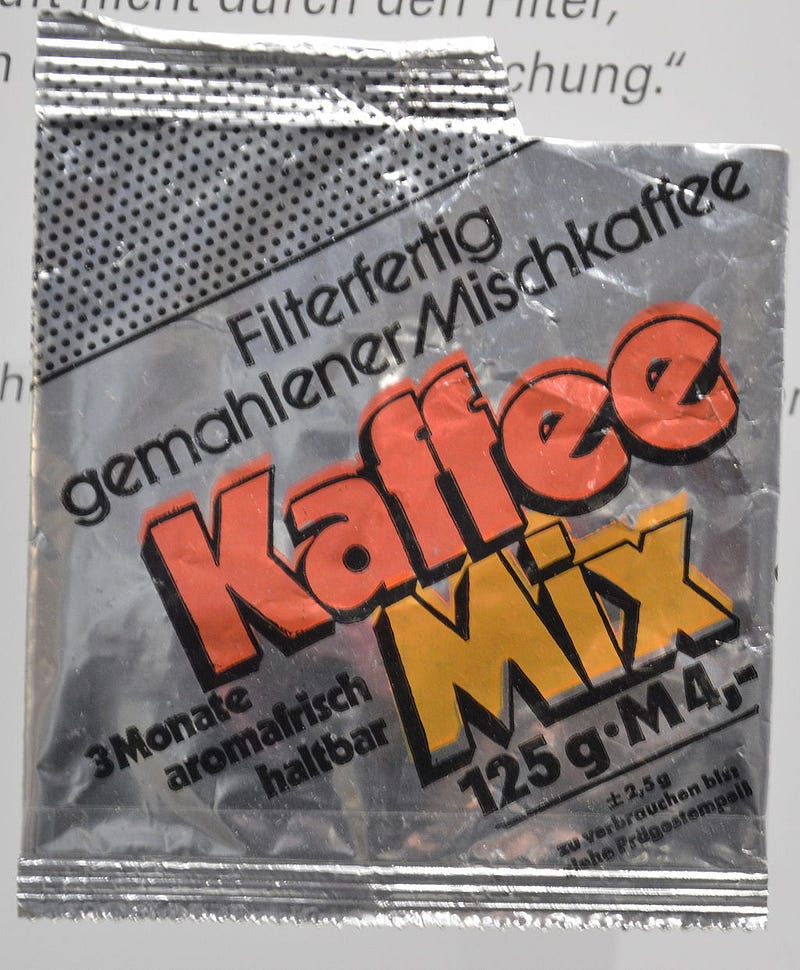

A famous illustration of the weakness of the East Germany economy was the “Coffee Crisis” in late 1970s, when the country faced financial challenges and was unable to import coffee, and had to create the famous “Coffee mix”, mixing coffee with other poorly transformed products.

The arrival of Gorbachev as head of the Soviet Union further complicated the situation for East Germany. Gorbachev made clear that things were going to change, and that people would have to choose. When other countries in Eastern Europe started economic and political reforms, Honecker decided to keep its stance till the end. Influenced by the events in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and perhaps the “Gorbymania” too — the name given to the popularity surrounding Gorbachev especially in Western countries; East Germans people started to ask for reforms, but also something extremely symbolic for East Germany : the freedom of travel. A threat to the key component of East Germany : the Berlin Wall. The requirement for the “workers paradise” to hold. Something that became so entrenched in East German identity, both for its people and leadership, that its disappearance was respectively hoped and feared.

East Germany responded as usual to people’s discontent : crackdown on protesters and gunshots on people trying to cross the Berlin Wall. The growing discontent was so huge that at one point, the leadership came to the conclusion that ousting Erich Honecker was the sole solution. On 18 November 1989, Erich Honecker was ousted in favor of Egon Krenz (1937).

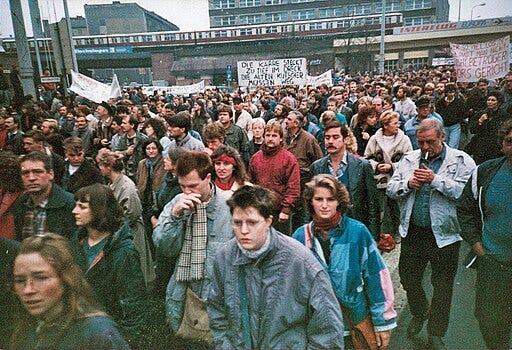

Even with good will, Egon Krenz couldn’t have been able to stop the crisis, and inevitable collapse of East Germany. Set apart the discontent over the economic situation, the fact remained that people were willing to be free. The best illustration was the Refugee crisis of September–November 1989 leading to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. People from East Germany were seeking something far more important for them than mere materialistic comfort (something, ironically, extremely important in East Germany) : meaningful life and freedom on all terms : thinking, speaking and traveling. There is nothing more disastrous for a regime (both inside and outside) than images across the world showing people, not marching in the street to get pay rises or more food, but moving together and in large numbers to onboard trains, cars and or even move by foot to leave their own countries. The most spectacular event was probably the invasion of the West Germany embassy in Prague where people from East Germany seeked refuge. Also disastrous to East Germany was the idea of sending people outside the country on sealed trains for them shedding tears of joy and to be greeted on television by West Germans.

The Alexanderplatz demonstration on 4 November 1989 with nearly one million protesters was the clearest sign that things had to change once for all. Günter Schabowsk was invited, like other leaders, to speak in front of everyone. We can say everything regarding his actions but this kind of move — especially when you are hated and hooted by everyone— is courageous.

Ultimately, the final act of East Germany had nothing to do with economy or even politics — not in the traditional sense at least. It was probably only with a symbol — the Berlin Wall — that became so deeply associated with East Germany, so important for its leadership and extremely problematic for its own people, that its collapse was the required climax for everything to change.

Was the reunification — after the hope, struggle, tears and celebrations — easy and as good as people expected it to be in East Germany ? While it was a good and required thing — the natural reunification of a people — it could only have been difficult. For decades, a country — East Germany — was totally disconnected from social, political and economic realities of the West. Merging with the West couldn’t have been easy. On both sides, people suddenly discovered that despite their dream of living together, they had been living in two different universes for decades. The toll was mainly financial and economical for the West : it was required to sustain all public services and many companies for a long time. For the East, the toll was probably far more severe : people had to become accustomed to a completely new world, while their past one suddenly disappeared. Their past systems were dismantled, their companies restructured and beliefs erased.

Sometimes, in a very unfair manner. Many past soldiers and officers of the National People’s Army (East Germany armed forces) were discharged and entitled to lower pension because they were considered as part of a foreign army. The Treuhandanstalt in charge of managing past state-owned businesses in East Germany was heavily criticized. Tensions were so high that its first director, Detlev Karsten Rohwedder, was assassinated (possibly by the Red Army Faction). The stigma surrounding the Stasi (political police of East Germany) is so important that even people like Lothar de Maizière (who won the 1990 last and only democratic elections in East Germany) was dismissed from the government of Helmut Kohl in 1990 after it was discovered he worked as an undercover agent for the Stasi — a fact far from unusual in East Germany with nearly 174 000 informants or possibly 3% of East Germany population. While not always disrespectful, the term “Ossi” is sometimes used to remind people that they come from a supposedly less developed country. A reminder for many people that they were born and grew in a country that didn’t exist anymore, not only as a political entity, but also in a cultural and social way.

The announcement of the opening of East Germany borders even at Berlin, leading ultimately to the collapse of Berlin Wall, is still something Günter Schabowski should be credited for. Something he did while leaving the press room and going back home to sleep as usual. Like on a normal day. He is probably the only one to have expressed remorse over his past actions and GDR legacy. The one who made history by mistake. The man who was lucky enough that everyone — from border guards to military officials — understood that it was over, and let people go without harming them.

But while his mistake was something invaluable for the greater good, he was far from being innocent. Like many other past officials of East Germany, he was convicted with other people like Egon Krenz for his responsibility over the deaths of several people who tried to escape East Germany. He was sentenced to several years in jail. His relationship with his past colleagues were difficult. Some East Germans are nicknamed “Ossie”, Gunter was nicknamed “Wendehals” (Derived from the bird “Wryneck” who can turns its head by 180°)

Whatever… Ruhe in Frieden / Günter Schabowski / 1929–2015

Laisser un commentaire