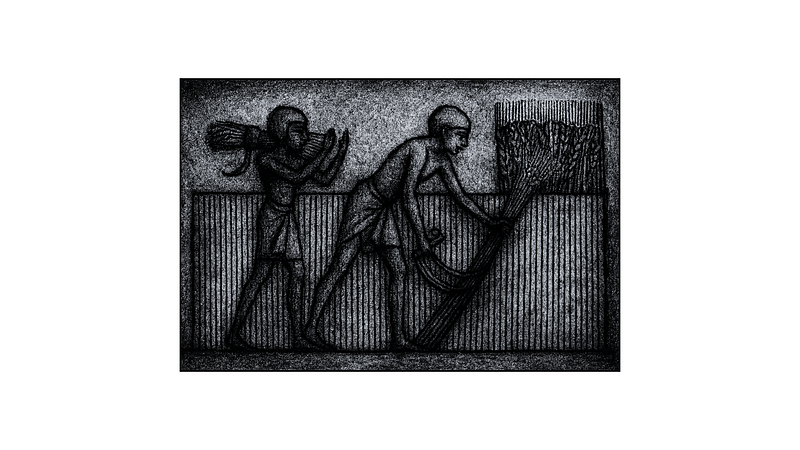

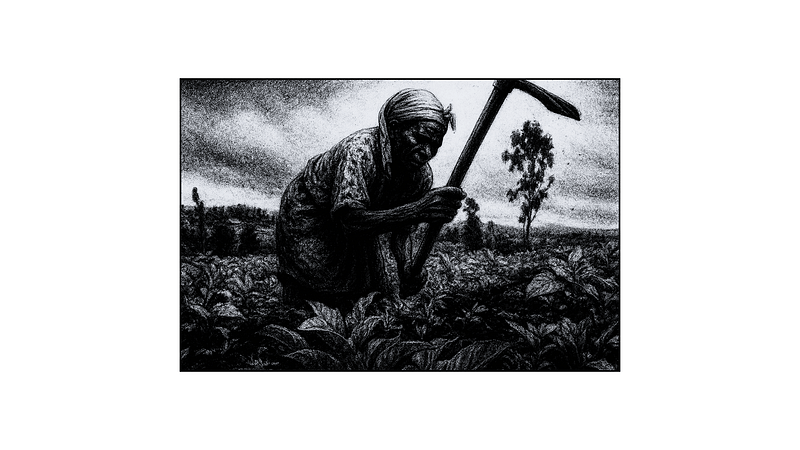

The hoe is perhaps the oldest tool in human history — predated only by the “digging-stick”. Today, this simple agricultural tool is definitively associated with subsistence farming — critical to millions of people across the world. And especially in what is called the “hoe-cultivation belt”. In this small essay, I’m going to explore the importance of this small tool both in the past, present and also future.

La houe est peut-être l’outil le plus ancien de l’histoire de l’humanité, précédé seulement par le « bâton à creuser ». Aujourd’hui, cet outil agricole simple est définitivement associé à l’agriculture de subsistance, essentielle pour des millions de personnes à travers le monde. Et en particulier dans ce qu’on appelle la « ceinture de culture à la houe ». Dans ce petit essai, je vais explorer l’importance de ce petit outil dans le passé, le présent et aussi l’avenir.

The “hoe-farming” concept was introduced by Eduard Hahn in his 1920 book “Niederer Ackerbau oder Hackbau?“ (In English “Low-intensity farming or hoe cultivation?”) under the German name “Hackbau”. Extremely basic, simple and versatile, the hoe can be used for cultivation but also for plenty of agricultural tasks — especially to remove weeds and roots. Hoeing is labor intensive, but doesn’t require machines or animals.

Le concept d’« agriculture à la houe » a été introduit par Eduard Hahn dans son ouvrage publié en 1920, intitulé « Niederer Ackerbau oder Hackbau ? » (en français « Agriculture à faible intensité ou labour à la houe ? ») sous le nom allemand « Hackbau ». Extrêmement basique, simple et polyvalente, la houe peut être utilisée pour la culture, mais aussi pour de nombreuses tâches agricoles, notamment pour éliminer les mauvaises herbes et les racines. Le travail à la houe est très physique, mais ne nécessite ni machines ni animaux.

The exact period of hoe invention can’t be traced perfectly (perhaps 10 000 BC ?) , but it’s clear that this tool is extremely old in agricultural history. The only preceding agricultural tool could be the “digging-sick” in some regions of the world. For millennia, it was the tool used to make furrows before the advent of the plough — or the ard in several regions. It was a topic of debate for past civilizations as demonstrated with the Sumerian poems “Debate between the hoe and the plough” — circa 3 millennium BC. The key difference between the ard and the plough, is that the “split” the soil while the plough makes furrows — in depth, which has the effect of aerating the soil and facilitating sowing, particularly in clay soils.

La date exacte de l’invention de la houe ne peut être déterminée avec précision (peut-être 10 000 avant J.-C. ?), mais il est clair que cet outil est extrêmement ancien dans l’histoire de l’agriculture. Le seul outil agricole qui l’a précédé pourrait être la « pioche » dans certaines régions du monde. Pendant des millénaires, c’était l’outil utilisé pour creuser des sillons avant l’avènement de la charrue — ou de la charrue à soc dans plusieurs régions. Il a fait l’objet de débats dans les civilisations anciennes, comme en témoignent les poèmes sumériens « Débat entre la houe et la charrue » — datant d’environ 3 000 ans avant J.-C. La différence essentielle entre la charrue et la charrue à soc est que la charrue « fend » le sol tandis que la charrue creuse des sillons en profondeur, ce qui a pour effet d’aérer le sol et de faciliter les semailles, en particulier dans les sols argileux.

With the advent of the plough (invented around 3500–3000 BC), the distinction between “plough-civilization” and “hoe-civilization” became important because the plough allows for larger land cultivation while the hoe is made for small land cultivation. That’s the reason why most of the key civilizations emerged in “plough-cultivation” zones, especially because the plough allows mass production of cereals — a key agricultural product tied to bread, generally considered a staple food of civilization as it required large-scale farming, processing, transport and refinement. The advantage of the plough is that it allows farmers to cultivate “heavy” and fertile soils. Something you can’t easily do with a hoe — or a “digging stick”. Another topic is that large-scale farming with ploughs contributes to the creation of large and scalable exploitation.

Avec l’avènement de la charrue (inventée vers 3500–3000 avant J.-C.), la distinction entre « civilisation de la charrue » et « civilisation de la houe » est devenue importante, car la charrue permet de cultiver de plus grandes surfaces, tandis que la houe est destinée à la culture de petites parcelles. C’est la raison pour laquelle la plupart des civilisations clés ont émergé dans les zones de « culture à la charrue », notamment parce que la charrue permet la production massive de céréales, un produit agricole essentiel lié au pain, généralement considéré comme un aliment « civilisationnel » car il nécessite une agriculture, une transformation, un transport et un raffinage à grande échelle. L’avantage de la charrue est qu’elle permet de cultiver des sols « lourds » et fertiles. Ce qui est difficile à faire avec une houe ou un « bâton à creuser ». Un autre sujet est que l’agriculture à grande échelle avec des charrues contribue à la création d’une exploitation importante et évolutive.

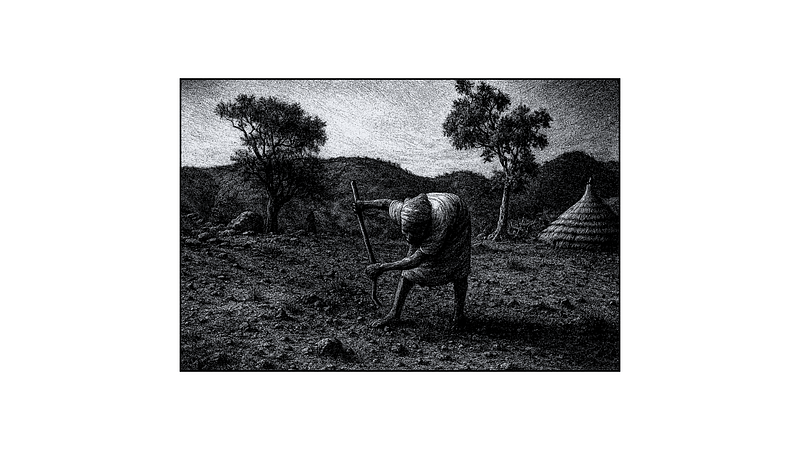

But the plough can’t be used everywhere. When the soil is too humid or sandy, the plough can contribute to its degradation. That’s why the hoe or stick is the best option. In several regions, due to geographic and topographic constraints, it’s impossible to use animal traction — lack of space to use it properly for example. That’s the case in the Andes and several parts of South-Asia. It’s also worth noting that in several regions of the world, subsistence farming is part of the culture. The idea of “large-scale” farming would be detrimental to the culture and habits of the people. And finally, the financial investment required for plough farming makes it impossible to implement in several regions.

Mais la charrue ne peut pas être utilisée partout. Lorsque le sol est trop humide ou sableux, la charrue peut contribuer à sa dégradation. C’est pourquoi la houe ou le bâton sont les meilleurs outils. Dans plusieurs régions, en raison de contraintes géographiques et topographiques, il est impossible d’utiliser la traction animale, par exemple par manque d’espace pour l’utiliser correctement. C’est le cas dans les Andes et dans plusieurs régions d’Asie du Sud. Il convient également de noter que dans plusieurs régions du monde, l’agriculture de subsistance fait partie de la culture. L’idée d’une agriculture « à grande échelle » serait préjudiciable à la culture et aux habitudes des populations. Enfin, l’investissement financier nécessaire à l’agriculture à la charrue rend son utilisation impossible dans plusieurs régions.

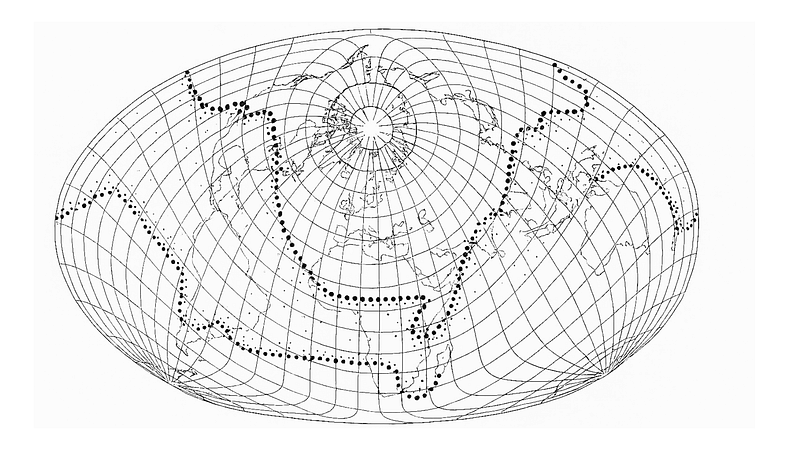

The above map illustrates the approximate zone of what is now called the “hoe-cultivation belt”. As you can see, most of the areas are concentrated around the Equator : Oceania, Amazonia, Sub-Saharan Africa… These regions (especially in Africa) are among the poorest in the world and sometimes the most unstable — with the exception of South-Asia. The weather conditions in equatorial regions are also creating major challenges for standard agriculture. Despite this situation, nearly 2.5 billion people relied on “subsistence farming” across the world, and nearly 500 million of small farms (less than 4 acres) exist in the world.

La carte ci-dessus illustre la zone approximative de ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui la « ceinture de culture à la houe ». Comme vous pouvez le constater, la plupart des zones sont concentrées autour de l’équateur : Océanie, Amazonie, Afrique subsaharienne… Ces régions (en particulier en Afrique) comptent parmi les plus pauvres du monde et sont parfois les plus instables, à l’exception de l’Asie du Sud. Les conditions météorologiques dans les zones équatoriales posent également des défis majeurs à l’agriculture traditionnelle. Malgré cette situation, près de 2,5 milliards de personnes dans le monde dépendent de l’« agriculture de subsistance », et près de 500 millions de petites exploitations (moins de 2 hectares) existent dans le monde.

In conclusion, should we force these people to abandon the hoe ? Relegate it to history museums? That would undoubtedly be a mistake and, above all, absurd. First of all, this tool is extremely versatile — it can be used for cultivation, soil maintenance and even gardening. Secondly, some regions of the world are not suited to large-scale agriculture due to climatic conditions, culture, soil quality, etc. What should concern us is poorly planned or managed subsistence farming. This danger is already evident in deforestation, shifting cultivation and slash-and-burn agriculture. The real question is rather how to rehabilitate it and, above all, how to make better use of it where it remains indispensable.

Pour conclure, devons-nous forcer ces gens à abandonner la houe ? La reléguer dans les musées historiques ? Ce serait sans doute une erreur et surtout une absurdité. Tout d’abord, cet outil est extrêmement versatile — on peut cultiver, entretenir les sols ou encore faire du jardinage. Ensuite, des régions du monde ne sont pas adaptées à l’agriculture de grandes surfaces — conditions climatiques, culture, qualité des sols… Ce qui devrait nous inquiéter c’est une agriculture de subsistance mal raisonnée ou encadrée. Un danger déjà visible avec la déforestation, l’agriculture itinérante ou encore l’agriculture sur brûlis. La vraie question serait plutôt comment la réhabiliter et surtout mieux l’utiliser là où elle reste indispensable.

The Hoe having engaged in a dispute with the Plough, the Hoe addressed the Plough: “Plough, you draw furrows — what does your furrowing matter to me?”

La houe, après s’être disputée avec la charrue, s’adressa à celle-ci : “Charrue, tu traces des sillons, mais en quoi cela me concerne-t-il ?”

Ressources :

- «Hoe shifting cultivation in east African subsistence culture» (Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 2006)

- «Subsistence Food Production Practices: An Approach to Food Security» par S.A. Rankoana (2017)

- «The Heavy Plough and the Agricultural Revolution in Medieval Europe» (Andersen, Jensen & Skovsgaard)

- «Energy inputs and outputs of subsistence cropping systems» (Norman, 1978)

- «The Contribution of Subsistence Agriculture to …» (2012)

Laisser un commentaire