Sex education is a complex and sometimes difficult topic across the world. How to properly introduce sexuality to young boys and girls ? At which ages ? With what kind of words ? The idea of this article is to recall the long and difficult history of sex education programs, and the possible perspectives of these classes. The topic will be discussed chronologically, from earliest “Moral and Hygiene” programs to modern Sex-Ed classes. For simplicity, the main countries selected for this article are the United States, the United Kingdom and France. For recent history, some discussions are added regarding the issues in the “developing-world”.

- 19th Century: Moral and Hygiene-Based Beginnings

- Early 20th Century: The Social Hygiene Movement

- Mid-20th Century: Medicalization and Resistance

- 1960s–1970s: The Sexual Revolution and Comprehensive Education

- 1980s: The HIV/AIDS Crisis

- 2010s–Present: Digital Era and Cultural Debates

19th Century: Moral and Hygiene-Based Beginnings

- 1820s–1850s — Early “moral education” movements in Europe and North America addressed sexual behavior indirectly through religion and morality.

- 1870s–1890s — The rise of public health campaigns against prostitution and venereal diseases introduced the first “social hygiene” lessons, especially in Britain, Germany, and the U.S.

The earliest forms of sex education classes were generally religious in their forms, and “morality-oriented”. It meant that the goal of these classes was not to teach about reproduction and sexual health, but to clearly orient the sexuality toward a religious and moral goal. The idea of “health-oriented” sexual education campaigns emerged during the Industrial Revolution. The growing population in industrial towns led to an increased use of prostitution by workers — mainly men. At the time, during the 1870s-1890s, many modern solutions were non-existent or prohibitive : contraception, condoms, medications… It meant that several diseases were untreatable, the most famous and deadly one being the syphilis — well-known and documented, especially for the unfortunate and painful fate of people suffering from third stage syphilis, leading to bones and nerves damages. The topic remained controversial and the new programs, while introducing the “health” concept, were still focused on abstinence and moral values.

In the United States, the Comstock Laws (1873) criminalized the mailing of “obscene” materials — which included contraception and information about sex. This made formal sex education legally risky and framed sexuality as indecent. In the United Kingdom, the Contagious Diseases Acts (1860s) allowed police to forcibly examine women suspected of prostitution for venereal disease. Even though these laws were repealed by 1886 after feminist protest, they cemented the idea that sexual behavior was a public health issue under state control.

Early 20th Century: The Social Hygiene Movement

- 1900–1920 — The Social Hygiene Movement gained influence, framing sex education as a public health necessity.

- 1914: The American Social Hygiene Association was founded. Lessons focused on preventing disease and promoting moral behavior, not sexual rights or pleasure.

- 1910s–1920s — Some U.S. schools began offering formal lectures on “human biology” and “reproduction,” usually emphasizing abstinence.

With growing secularism in many societies and countries, a shift was noticeable from moral/religious programs to public health programs. The topic began to be progressively controlled by the public sector with the emergence of public health services. It was during this period that few experiences were put in place to introduce human biology and reproduction. A necessary step to handle the topic in the right way : sexual rights, pleasure, communication, feelings and so on.

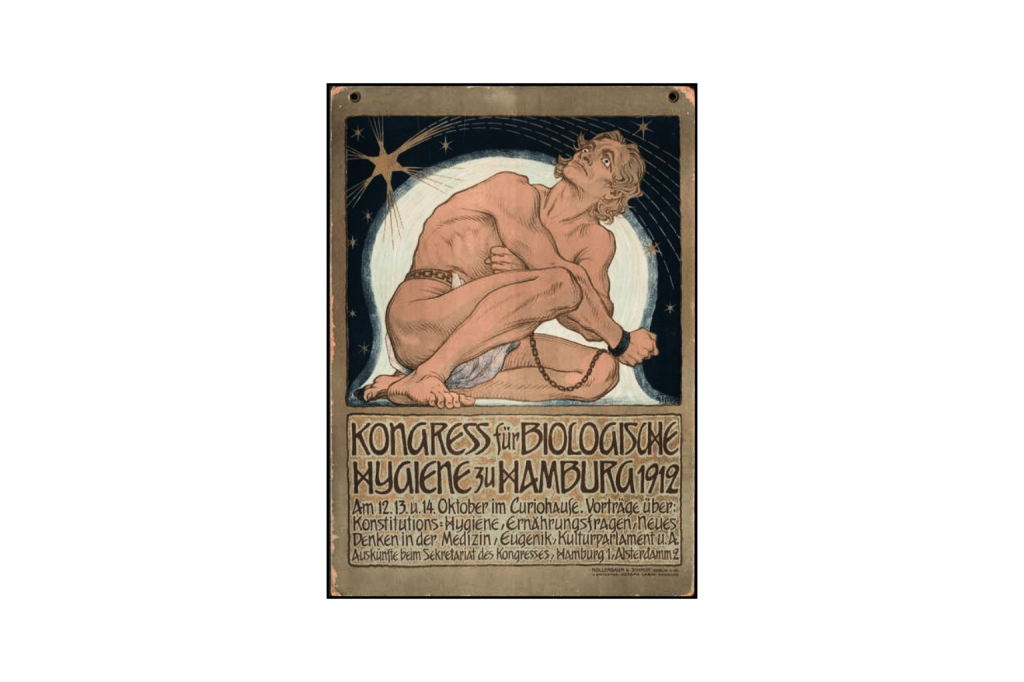

A key event across the world — or at least in several countries — halted the progress of sexual education programs : natalism — promotion of or advocacy for childbearing. After the enormous loss of lives — especially men — following WWI, nearly all involved countries focused on birth rates. More problematic during the “interwar-period” (1920s-1930s), several countries adopted eugenics politics, especially the United States and Nazi Germany.

In the United States, the Social Hygiene Movement continued from the early 1900s into the 1920s, now blending public health, eugenics, and moral reform. Organizations such as the American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA) promoted chastity before marriage and “clean living” as patriotic virtues. Educational materials warned of venereal diseases but rarely discussed contraception or pleasure. In the 1930s, eugenic ideas gained prominence: “fit” families were encouraged to reproduce, while marginalized groups — immigrants, African Americans, people with disabilities — were often subject to coercive sterilization. State “hygiene” classes in schools taught basic anatomy and reproduction as civic duty, not as personal knowledge.

In Britain, early twentieth-century sex education remained bound to moral and religious discourses. The Social Hygiene Council and Moral Welfare Council organized lectures warning against prostitution and “moral decline.” Schools rarely mentioned sexual topics except through biology lessons about reproduction. During the interwar years, British authorities also linked sexual health to national efficiency. Eugenic rhetoric influenced public policy — encouraging “sound families” and discouraging the reproduction of the “unfit.” The rise of venereal disease during both World Wars led to government campaigns such as “Keep Fit for Victory” and “VD: Don’t Let It Cripple You.”. By the 1940s, the concept of sex education had a fragile legitimacy: acceptable only when framed as public health for national survival. Pleasure and gender equality remained taboo.

After the devastation of World War I, France adopted an overtly pronatalist policy, fearing national decline. Sex education was suppressed under the Law of July 31, 1920, which criminalized any public information about contraception or abortion. Instead, schools and public discourse emphasized family values, maternal virtue, and patriotic motherhood. The Alliance nationale pour l’accroissement de la population (National Alliance for Population Growth) led mass propaganda campaigns celebrating large families. Posters such as “Famille nombreuse, famille heureuse” (“Large family, happy family”) idealized motherhood as a civic duty. When sex education was mentioned, it was only to highlight biological reproduction within marriage, never desire, contraception, or equality. The Code de la Famille (1939) institutionalized this ideology by rewarding families with many children and punishing abortion. Thus, French “sex education” between the wars served as an instrument of moral control and demographic policy.

Under the Nazi regime (1933–1945), sex education became part of racial ideology. The state promoted the fertility of “racially pure” Aryans while discouraging or forcibly preventing reproduction among Jews, Roma, and other groups labeled “undesirable.”. Youth organizations such as the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM) taught girls that their highest duty was motherhood for the Führer. Instruction focused on hygiene, racial science, and obedience — not sexuality or mutual respect. The Lebensborn program (1935 onward) provided state support for unmarried “racially suitable” mothers to give birth to “Aryan” children. Contraception and abortion were strictly forbidden for “German” women but encouraged or enforced among others. Sexual education thus became an explicit tool of biopolitical control, merging eugenics, nationalism, and misogyny.

Mid-20th Century: Medicalization and Resistance

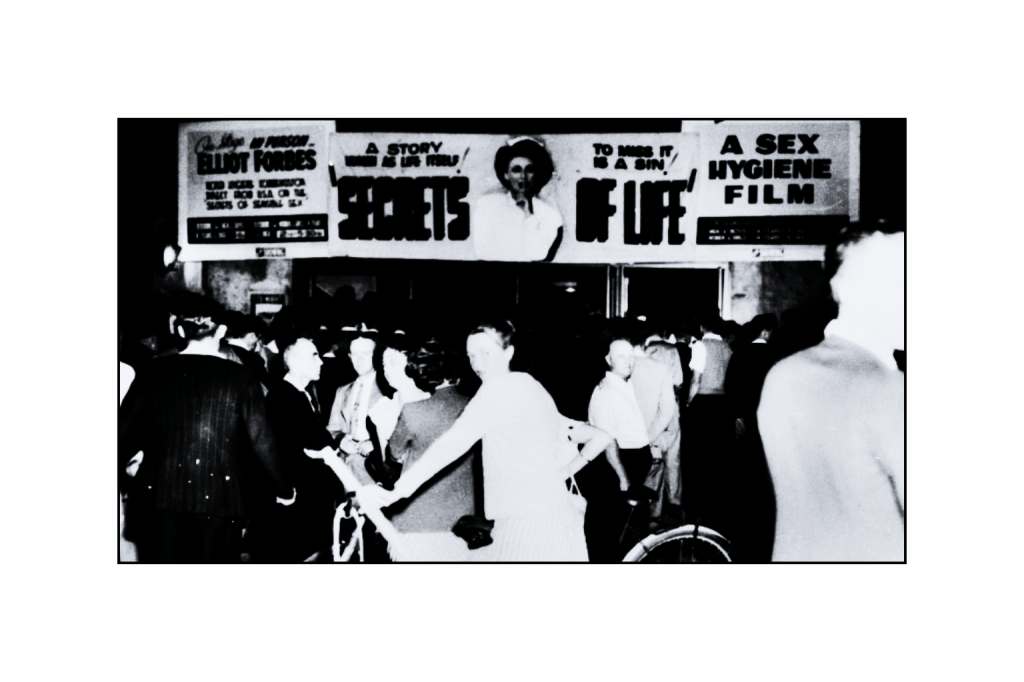

- 1940s–1950s — With World War II and postwar fears of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), governments began linking sexual behavior to national health. Films and pamphlets about venereal disease prevention became common.

- 1948 — Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (and later in the Human Female, 1953) challenged traditional views and sparked controversy, influencing later debates.

- 1950s–1960s — Conservative backlash limited progress; most education remained biological and moralistic.

The breakthrough regarding sexual education occurred with the infamous Kinsey’s Reports (Male and Female Sexuality) in 1948 and 1953. The reports were extremely innovative at the time of their release. For the first time, human sexuality was discussed in true scientific terms : survey, scales, male/female comparison, sociological issues and so on. A few years before, WWII had already forced authorities to prevent sexual disease spreading, especially among soldiers — a move that forced authorities to publish movies, pamphlets and even posters to discuss the topic.

1960s–1970s: The Sexual Revolution and Comprehensive Education

- 1960 — The contraceptive pill was introduced, revolutionizing reproductive autonomy.

- Late 1960s — Activism around women’s liberation and gay rights expanded the scope of sex education to include pleasure, consent, and identity.

- 1964 — The Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) was founded, advocating for comprehensive, science-based curricula.

- 1970s — Many European nations integrated sexuality education into health or social studies programs.

The 1960s-1970s, along with Kinsey’s Reports, were almost the most influential years on the evolution of sexual education : women’s rights activism, May 68 protests in many countries, contraceptive pills… All these events led to unavoidable change in sexual education programs. The shift was nearly complete in the 1970s with the introduction of “science-based” sexual education programs in European countries.

The Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), founded in 1964 by Dr. Mary Calderone, explicitly promoted “comprehensive sex education” in schools, including topics like anatomy, contraception, pleasure, and relationships — totally radical for the time. In many districts, parents and conservative groups fought to ban SIECUS-style curricula, calling them obscene or anti-family. Access to contraception was gradually liberalized: U.S. Supreme Court cases like Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) for married couples and Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972) for unmarried people made birth control legally accessible, which in turn made teaching about it more relevant. The birth control pill (1960) separated sex from reproduction for millions of women. Second-wave feminism insisted that understanding your own body, consent, and pleasure was political. LGBTQ+ rights activism (after Stonewall, 1969) began challenging strictly heterosexual frameworks.

In the United Kingdom, school “personal and social education” units began to include puberty, reproduction, and contraception in the late 1960s–70s. The Family Planning Act (1967) allowed local authorities to offer contraceptive advice, including to unmarried people, which indirectly normalized talking about contraception with youth. The Abortion Act (1967) legalized abortion (under certain conditions) in Great Britain, pushing sex ed to address unintended pregnancy as a solvable medical/social issue, not just a moral catastrophe.

In France, the Neuwirth Law (1967) legalized contraception information and later access to contraceptives. The Loi Veil (1975) legalized abortion under certain conditions. In 1973 and onward France began introducing “éducation sexuelle” in schools as part of health and civic responsibility.

1973 : récit des débuts agités de l’éducation sexuelle à l’école | INA

1980s: The HIV/AIDS Crisis

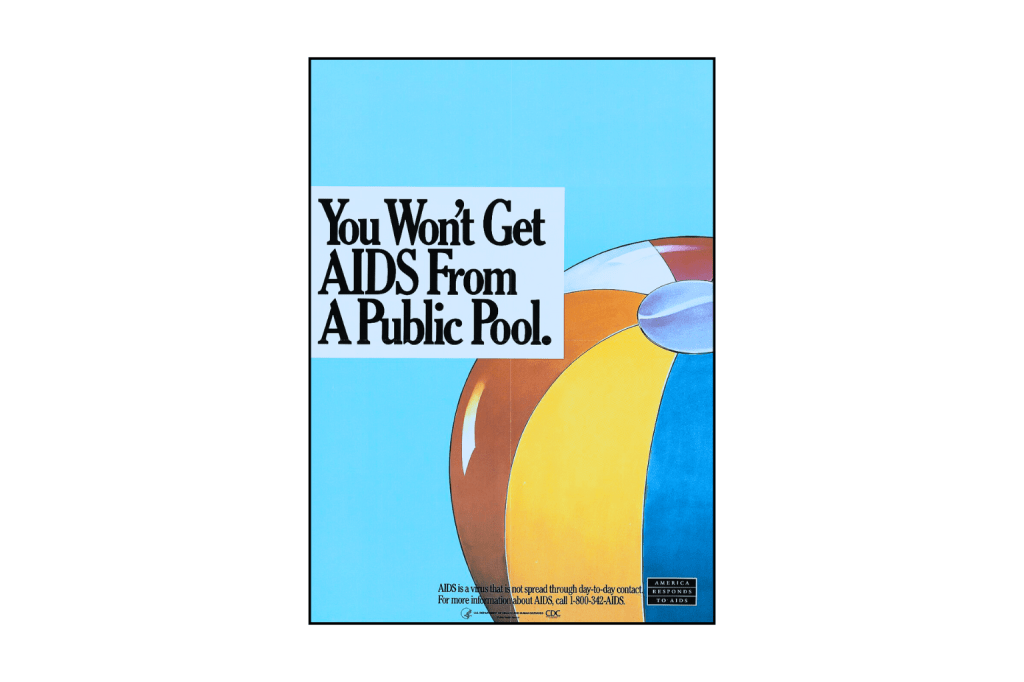

- The emergence of HIV/AIDS forced governments worldwide to confront the consequences of inadequate sexual education.

- Education shifted toward risk reduction, condom use, and destigmatization.

- 1986 — UNESCO and the World Health Organization (WHO) issued international guidelines promoting factual, preventive education.

The HIV/AIDS crisis was influential too regarding sexual education. The threat of this disease inevitably forced the public health sector in many countries to push in favor of condoms. In the US, the topic remained controversial against the “abstinence-based” programs. It was also during this period that the topic of homosexuality — and also several forms of sexuality like prostitution — was discussed not only as a stigma, but as a major public health topic. The HIV/AIDS crisis would ultimately force changes in public health programs, with a better emphasis on these vulnerable parts of the population (sex workers, homosexuals…). The next decade saw a consolidation of this movement with the International Conference on Population and Development (Cairo) (which recognized sexual and reproductive rights as fundamental human rights) and the introduction of the concept of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) gained prominence through UNESCO and UNFPA programs, emphasizing gender equality, consent, and diversity.

In the United States, HIV/AIDS forces schools, media, and governments to talk about condoms, needle use, and safer sex. LGBTQ+ activists and public health educators create some of the first openly queer-inclusive safer-sex materials. Starting in the 1980s and accelerating in the 1990s, U.S. federal funding increasingly supports abstinence-only education, especially under Title V (1996). These programs often prohibit discussion of contraception except to stress failure rates. States and school districts become battlegrounds: some adopt comprehensive HIV/sex ed; others mandate abstinence until marriage. The AIDS crisis humanizes the stakes of misinformation but also fuels homophobic backlash. Sex ed becomes a proxy fight over LGBTQ+ rights, gender roles, and religion in schools.

In the United Kingdom, the mass public health campaigns (“Don’t Die of Ignorance”) in the late 1980s openly explained HIV transmission and condom use. Schools expanded “sex and relationships education.”. Section 28 (1988) prohibited local authorities (including schools) from “promoting homosexuality.” This chilled honest, LGBTQ+-inclusive sex education for over a decade.

2010s–Present: Digital Era and Cultural Debates

- Global expansion of CSE faced political and religious resistance in several countries.

- 2018 — UNESCO published the updated International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education, setting global standards.

- The rise of the internet and social media has both empowered youth with access to information and complicated regulation due to misinformation and pornography.

- Current trends emphasize inclusive education addressing LGBTQ+ issues, consent, online safety, and gender-based violence.

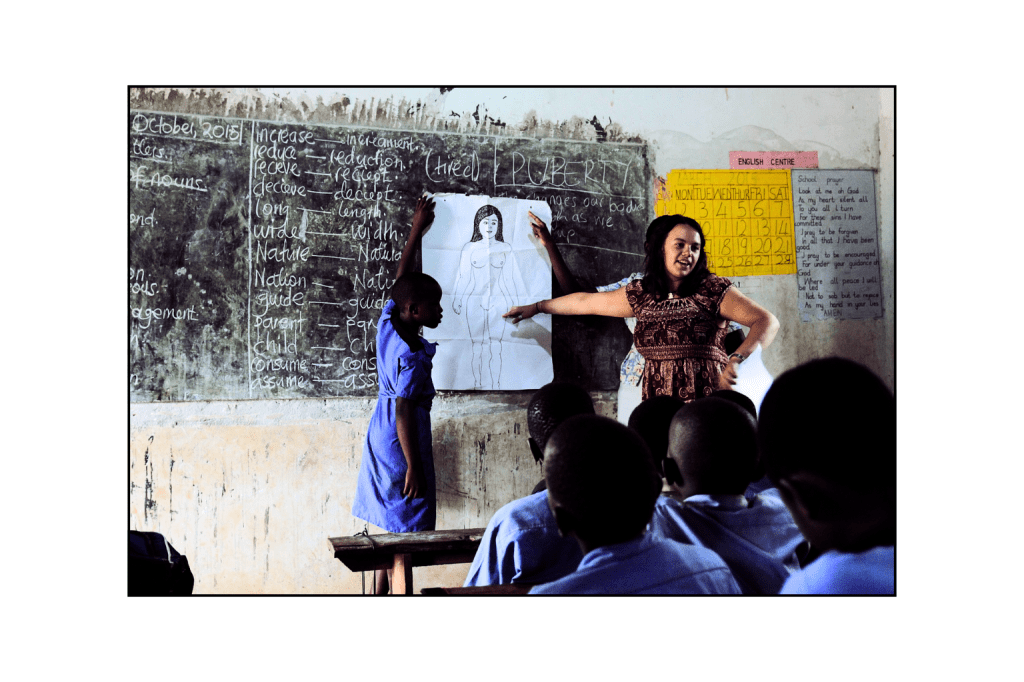

From the early 2000s/2010s and onward, the sexual education framework is still consolidating. In the United States, there is still a struggle between the “science-based” and “abstinence-based” sexual education programs. The current topic is how to properly educate young boys and girls in Southern countries, especially the poorest and unstable ones. Given increasing and concerning birth rates in several of these countries, the topic is now considered an international priority — both to educate young people and also to ensure a smooth birth rate control in these countries. The WHO (World Health Organization) now speaks of “Comprehensive Sexual Education” (CSE). A world defined as :

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) gives young people accurate, age-appropriate information about sexuality and their sexual and reproductive health, which is critical for their health and survival.

While CSE programmes will be different everywhere, the United Nations’ technical guidance — which was developed together by UNESCO, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women, UNAIDS and WHO — recommends that these programmes should be based on an established curriculum; scientifically accurate; tailored for different ages; and comprehensive, meaning they cover a range of topics on sexuality and sexual and reproductive health, throughout childhood and adolescence.

Topics covered by CSE, which can also be called life skills, family life education and a variety of other names, include, but are not limited to, families and relationships; respect, consent and bodily autonomy; anatomy, puberty and menstruation; contraception and pregnancy; and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

The modern consensus today on the topic of sexual education is that “abstinence-only” programs are ineffective and potentially harmful. The emerging questions — put aside the developing countries issues — is how to handle new societal challenges. Especially LGBTQ+ rights and religious renewal in modern countries. Sex-ed classes are still controversial for several reasons today. One of them is their importance given the possibility for young people to discover sexuality in a poor way on the internet — especially pornography. Something problematic when this kind of content is assimilated by young people as a “standard” for sexuality and relationships. Another concern is how to deal with human complexity in standardized sexual education classes, especially for LGBTQ+ and atypical people. All these topics won’t be explored here — as this article is about the history of sexual education — but are interesting and legitimate concerns.

Les cadres théoriques mobilisés incluent la psychanalyse classique (Sigmund Freud), les analyses critiques de la sexualité et du pouvoir (Michel Foucault), la théorie du genre (Simone de Beauvoir), la sociologie de la stigmatisation (Erving Goffman), ainsi que les études empiriques fondatrices sur les comportements sexuels (rapports Kinsey). Les sources publiques et institutionnelles comprennent les cadres de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) en santé sexuelle et reproductive, grossesse et accouchement, les recommandations de l’UNESCO sur l’éducation complète à la sexualité, les rapports de l’UNFPA sur les droits reproductifs, les textes du Conseil de l’Europe sur l’intégrité corporelle et le consentement, ainsi que les lignes directrices cliniques internationales sur l’intersexuation/DSD (Consensus de Chicago, ESPE), les troubles sexuels (EAU, ISSM, DSM-5-TR), et l’obstétrique et la néonatologie (FIGO).

- Sigmund Freud — Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality; Civilization and Its Discontents

- Michel Foucault — Histoire de la sexualité, vol. I; Surveiller et punir

- Simone de Beauvoir — Le Deuxième Sexe

- Erving Goffman — Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity

- Alfred C. Kinsey et al. — Sexual Behavior in the Human Male / Female

- World Health Organization (WHO) — Defining Sexual Health; Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Framework; Recommendations on Antenatal and Intrapartum Care

- UNESCO — International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education

- UNFPA — State of World Population Reports; My Body Is My Own

- Council of Europe — Human Rights and Intersex People

- Chicago Consensus Group — Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders

- European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (ESPE) — Clinical Guidelines for DSD

- European Association of Urology (EAU) — Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health

- International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) — Clinical Practice Guidelines

- American Psychiatric Association — DSM-5-TR: Sexual Dysfunctions

- International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) — Guidelines on Pregnancy, Childbirth and Neonatal Care

Laisser un commentaire