While studying British agriculture, I recently watched the documentary “Norfolk Past” produced with the help of the East Anglian Film Archive, recounting the history of this important agricultural region in the modern United Kingdom from the 1900s to the late 1960s using past movies, interviews and archives to illustrate how this small region evolved through several decades. An interesting account for me, and the reason for this post today to discuss both an important British county, with a rich history, and part of a broader agricultural system.

Table of contents :

- East Anglia

- British enclosure movement

- New crops : potatoes and carrots

- Agricultural improvements and British agricultural revolution

- The continuity of the British agricultural geography

- Yields improvements and agricultural struggles

- East of England

- What if the Cold War had met with East Anglia ?

- Concerns, future and revitalisation of British agriculture

- Conclusions

East Anglia

Early history

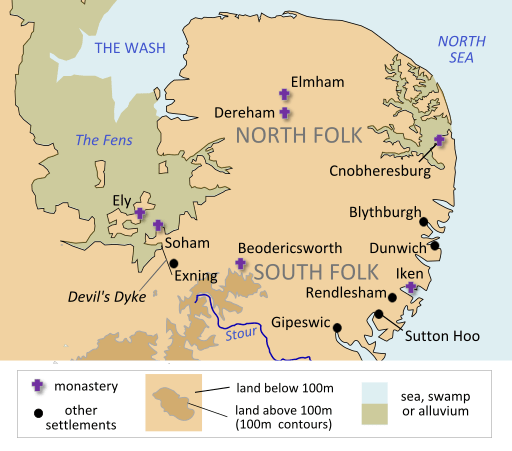

The East of England was probably the earliest region where the Anglo-Saxon settled in what is now the modern United Kingdom. The fact is that the region appears to have been inhabited as early as the Paleolithic too, and the region was also developed by the Romans (a famous site is the Burgh Castle, East of Norwich) when occupied from 43 A.D. to 410.

Before the Roman rule over what is now Norfolk, the place was inhabited by a tribe named the Iceni. With the arrival of the Romans, their territory was progressively seized by the Romans either by conquest or alliance. It led to the Boudican revolt in 60–61 A.D. crushed by the Romans after the defeat of the Iceni’s Queen Boudica, which was for some time in the 18th-19th century used as a political symbol in Britain.

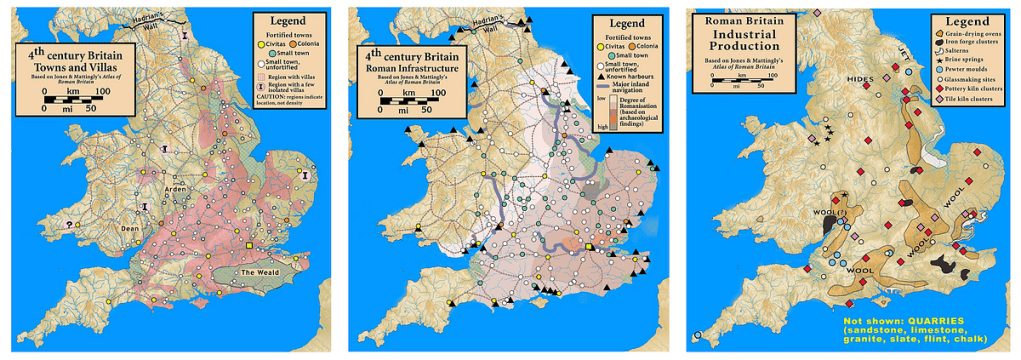

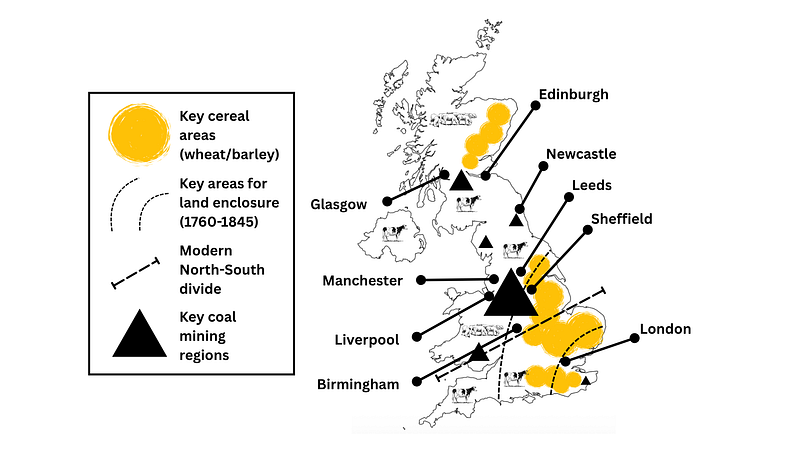

When we look at maps of Roman occupation of England, what emerges is the strong emphasis put on an area from modern East of England to modern Cornwall. Something mimicking the sometimes controversial — when it involves stereotypes and disrespect of course, not when it comes to understand agricultural, economical and political differences in the country — North-South divide line in modern United Kingdom :

With the ongoing collapse of the Roman Empire in continental Europe, the Roman armies in what is now England, left progressively the territory until 410; the year considered as the end of Roman rule over England. The East Anglian kingdom was formed in the 6th century, after the historical period called Dark Age England which lasted approximately from 407 to 577. This period known as “Sub-Roman Britain” is mysterious for researchers and historians because of the complete lack of historical and written sources.

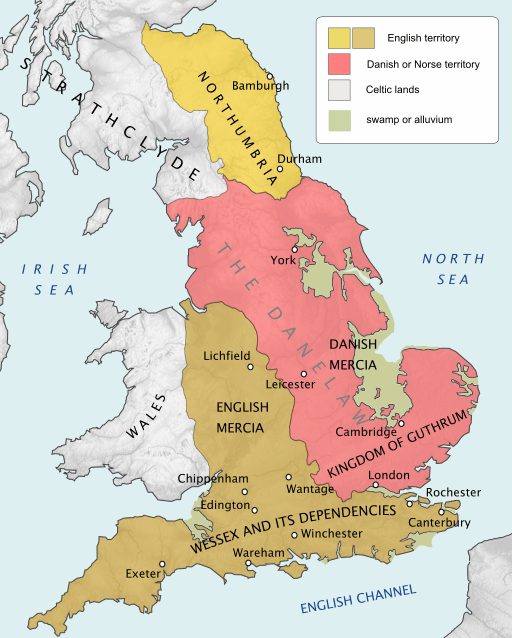

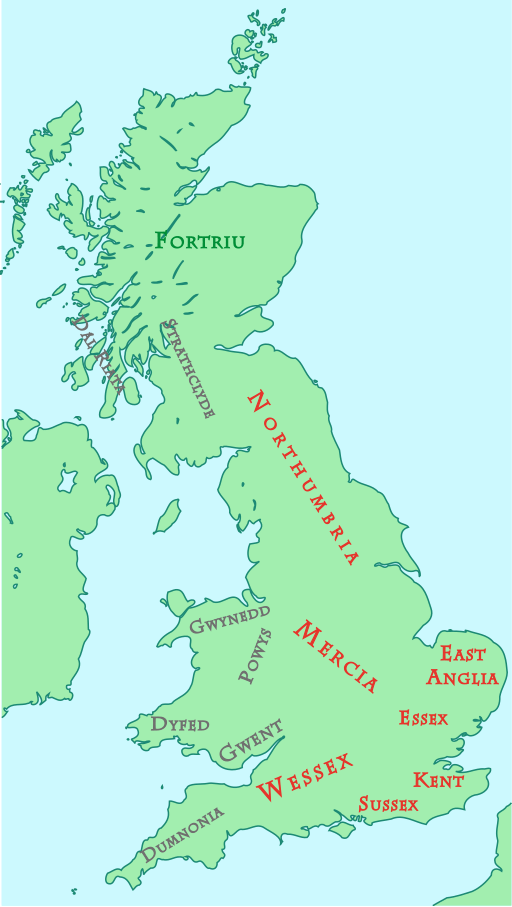

East Anglia was an independent kingdom for nearly 300 years before being incorporated into the Kingdom of England in 918. A period known as the Heptarchy in United Kingdom history, when the country was divided between seven kingdoms : East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex.

The story of East Anglia was, of course, more complex than that. The independent kingdom was even conquered by the Danish in 869 and incorporated in the Danelaw before its final incorporation into the Kingdom of England.

Here is a map to illustrate the geography of the historical kingdom of East Anglia (today, the region is divided between two British counties : Norfolk in the North, Suffolk in the South) :

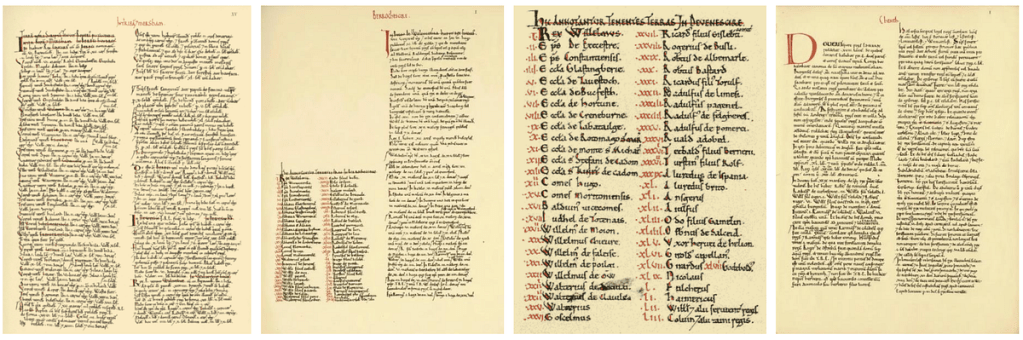

The Domesday Book

The next most important event of the country, and eastern regions, was the Norman Conquest, when William the Conqueror conquered England in the 11th century leading to a troubled and difficult period for the British isles. In 1086, William the Conqueror requested what is known today as the “Domesday Book”. The first survey of England to assess the state and resources of its new kingdom, and also to identify holders of the lands. This would be the sole large-scale survey in country history for centuries before the “Return of Owners Land” in 1873.

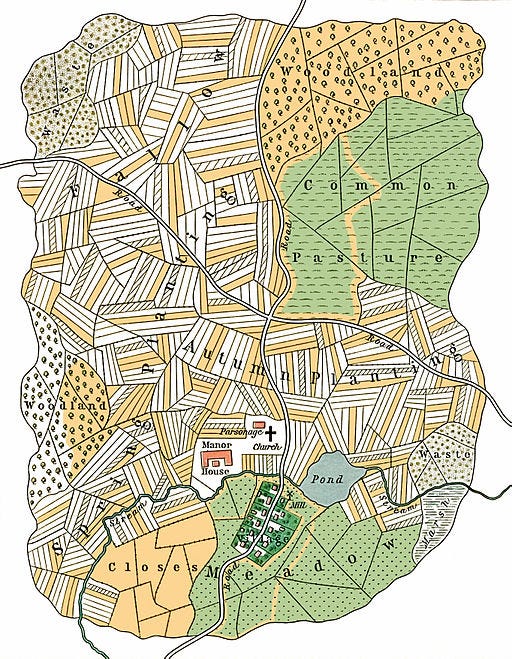

At the time of the Domesday Book, the agricultural landscape was dominated by the open-field system. A system dominated by what is called “strip-farming” : a field is cultivated by creating several strips of different crops. The open-field system in the United Kingdom disappeared over centuries through the enclosures, but in some places, the system is still in use as illustrated by this picture :

For those curious, the village of Laxton (Nottinghamshire) is considered today as the sole and last place in the United Kingdom where the open-field system is still preserved.

History went on

In the following centuries, Norfolk county increasingly became a major agricultural region of England, Great Britain and then the United Kingdom. The years between the 1200s-1300s saw great improvements for the Kingdom of England. A famous remnant of this relative prosperity is the Stokesay Castle in Shropshire, one of the finest and best preserved remnant of the fortified manor era :

Norfolk also has close ties to the British royal family with the presence of several royal estates in the county; as early as the 1100s-1200s with Castle Rising. We can mention for example :

- Castle Rising, residence of Queen Isabella (wife of Edward II), built around 1140

- Oxburgh Hall where Henry VII and his Wife Elizabeth in 1487

- Blickling Hall where Anne Boleyn (Henry VIII’s second wife) was born, and was owned by her family from 1499 to 1505

- Sandringham House and its 20 000 acre bought by Queen Victoria in 1862

Worth noting, Sandringham House was the place where Queen Elizabeth gave her first radioed Christmas Message in 1952, and the Queen’s first Christmas Broadcast on TV in 1957.

Troubled times : Black Death and Hundred Years War

The most severe disruptions halting these improvements in the Kingdom of England was first a severe agricultural crisis with the Great Famine of 1315–1317 which affected all continental Europe and England. Peasants faced severe crop failure and spread of disease amongst the livestock. The next major disruption was the Black Death between 1348 and 1349 which wiped out several villages and communities. For the sole England, the population fell from perhaps 4–5 million people to 2 million people. The consequences had lasting effects, especially on the demographic curve, with what is called the “plague centuries” during which England’s population stagnated at low levels. The death of so many people also led to a shortage of labor in the countryside, and people were asking for wage increases. The movement was not interpreted by authorities at this time as a natural consequence of economic changes. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 grew considerably to such an extent that peasants were marching on London, forcing the king to crackdown the revolt.

The following centuries were marked by several events in the Kingdom of England. The lasting Hundred Years War started in 1337, ended by a defeat in 1453. The numerous defeats before 1453 led to another major peasants revolt, the Jack Cade Rebellion, amid animosity between the king Henry VI and its people, debts, failing morale and fear of invasion. With relatively few times to recover, England entered a deeply troubled period named the War of the Roses (1455–1487) when the two main royal branches of the Plantagenet (House of York and House of Lancaster) fought over the throne of England. The country also faced several challenges in the 1600s with several civil wars opposing royalists and parliamentarians, the Three Kingdoms War and even a dictatorship under Oliver Cromwell. All these events ultimately led to the Glorious Revolution in 1688 when the British monarchy became parliamentary. On this topic, the fact is that the transformative process was already engaged for a long time in England. As a reminder :

- The Magna Carta signed in 1215 — even if suspended and re-activated several times — bound the power of the king regarding privileges of church and cities

- The Petition of Rights in 1628 introduced several rules regarding individual rights, especially in face of the penal system

- The Habeas Corpus of 1679 made mandatory for court to examine lawfulness of imprisonment

- The Bill of Rights is introduced in 1689

The country was also expanding its borders at this point with two Acts of Union. The first in 1707 with Scotland, and the birth of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. In 1800 with Ireland, and the birth of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

British enclosure movement

A major event in the centuries before the 1900s was the Kett’s rebellion in 1549 in Norfolk, when the decision was taken locally to implement on a large scale the principle of enclosure. In the past, lands were generally exploited collectively in Middle Ages England. The system, in a simple manner, was divided between what is called in the English agricultural system as :

- Commons : parish or local lord’s land where peasants were allowed to use it collectively and where decisions were generally taken together within the community to decide what to grow on the land

- Enclosures : the process of converting communal lands into private properties

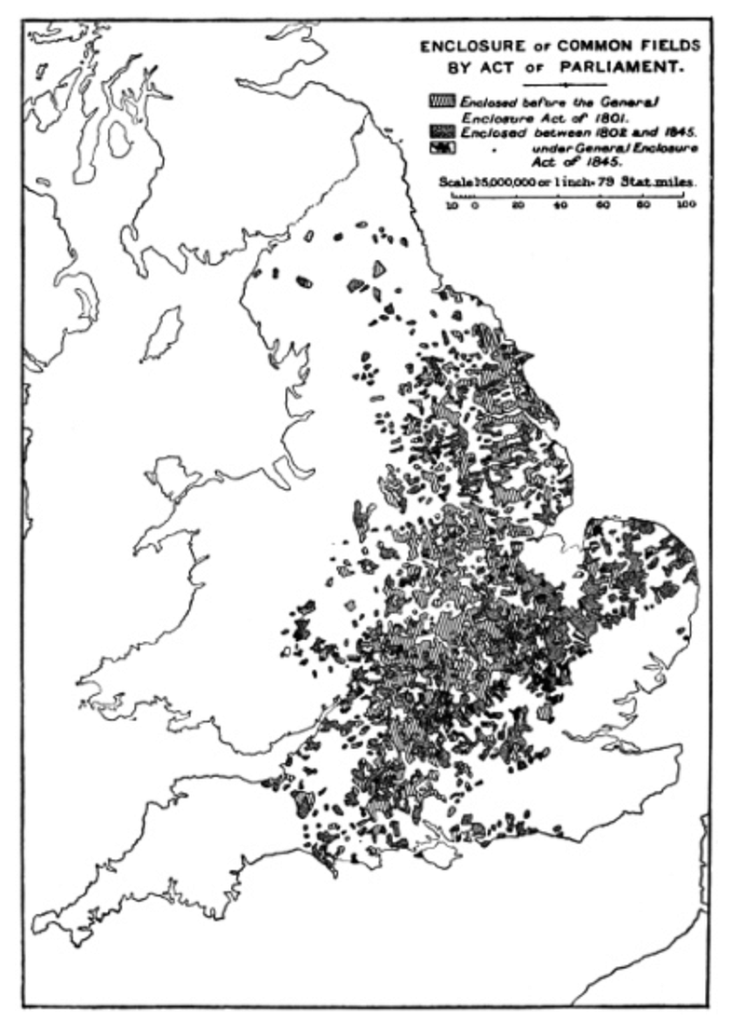

The goal of enclosure was to turn cropland into pasture for sheep and wool production (as a highly profitable industry in the past), and also to improve productivity in several areas when the agricultural system progressively shifted to a more capitalistic and capital intensive system. It occurred mainly between the 16th and 19th centuries, and it was done through local and/or informal agreements at the beginning, and then by “Enclosure acts” made by the Parliaments. Something that affected all of England, allowed for agricultural improvements, but also led to expulsion of many peasants, social unrest in many areas, and migration to cities in several parts of the country. The agricultural landscape of the United Kingdom at this time was similar to the openfield system. Something not to be mistaken with modern agricultural landscape where fields are not physically enclosed, but with an agricultural system where many fields and agricultural tasks were done together. Here is a map illustrating this point in Medieval Europe :

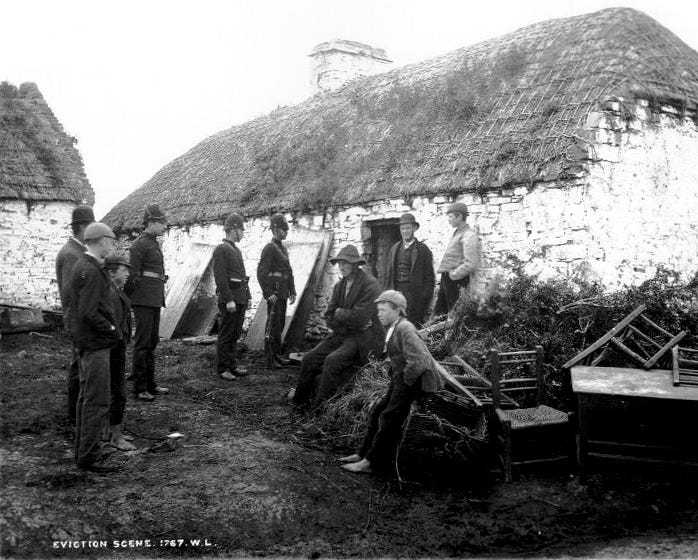

Some “campaigns” were particularly brutal for peasantry, like for example during the Highland Clearances in Scotland between 1750 to 1860. While not directly tied to the enclosures, several expulsions occurred during the 1879 Irish famine (Ireland as a whole was still part of the United Kingdom at this time). This kind of scene was very common unfortunately in Ireland at the time :

All these events were important factors leading ultimately to the independence of Ireland in 1922. Here is a map to illustrate the extent of enclosures across the country :

The word “enclosure” could be a bit misleading for French people like me (because it evokes the idea of putting a barrier around a field). But from a mere agricultural perspective, it would be more of what is called in French “Remembrement” or land consolidation in English, either by converting communal lands to private properties, and also by removing past fences (with small walls) to create bigger properties. Something that was essential to improve productivity. While noting that in France, the idea was to aggregate inefficient small and dispersed small plots into bigger ones. In what is now the United Kingdom, it was done to privatise commons. The Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) put a lot of pressure on the British agricultural system with the Continental blockade. Grains prices were rising, while the country had to feed both its army and population. This situation led to more efforts in favor of enclosure across the country, fostering the disappearance of the commons system.

Regarding the wool industry discussed earlier and deeply tied to the enclosures, it’s important to discuss the history of the wool industry in the United Kingdom. In early times, in Europe, historical textiles production areas were located in the Flanders region and Bruges, Ghent and Ypres cities (modern Belgium and France). The area is closely located to the modern United Kingdom, and it naturally led to exports of British wool to the continent. The trade was so crucial and profitable that in the 14th century, it was turned into an object to symbolize it : the “Woolsack”. A large red seat filled with British wool. Wool became a major source of tax revenue for centuries in what is now the modern United Kingdom. Something of an oddity today : when the wool industry faced difficulties, it was even made mandatory by the Caps Act in 1571 (except for nobility) to wear a woolen cap on Sundays and holidays. Wool industry prosperity peaked during the Industrial Revolution especially in Leeds region, but progressively disappeared in the following decades with increasing imports from the Far East. These abandoned mills in Leeds (some demolished now) are the last remains of this glorious industrial past :

New crops : potatoes and carrots

Then the United Kingdom had plenty of products grown on its soil for centuries. The country was well known for its cereals (barley, wheat, oats and rye), legumes (peas and beans), vegetables (turnips, leek, onion…) and fruits too (apples and pears). But the range of available crops remained quite limited for a long time. One of the most groundbreaking crops — in the UK and elsewhere — was the potatoes. It was imported back in 1586 by Sir Walter Raleigh from America. Potatoes are well-known for being both nourishing and extremely interesting to produce, with high yield per hectare. Potatoes proved well-suited to the British climate, and being — like in many other countries — associated with lower class status, progressively becoming one of the most consumed products in the United Kingdom. Another product was carrots (the orange ones) in 1590. We can also mention corn (maize) too even if their production remains limited.

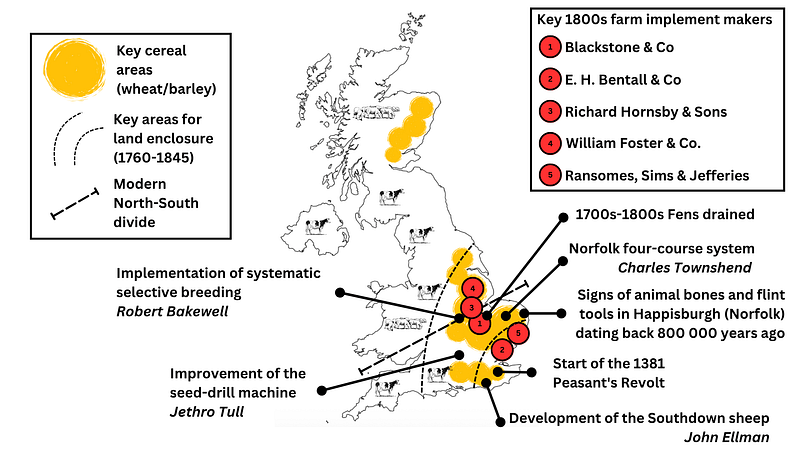

Agricultural improvements and British agricultural revolution

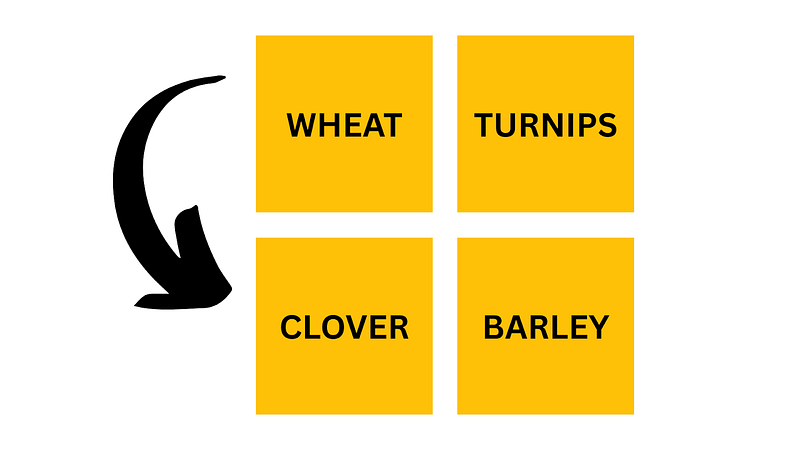

The map is also very interesting for another topic not related to enclosure : many major agricultural improvements occurred in the area of the enclosure campaign and especially eastern counties. The East of the country was the home of several major and critical agricultural improvements over several centuries, especially regarding crop yields, leading to the British Agricultural Revolution during the 18th century. The most critical innovations were :

- The Norfolk four-course system, invented in Waasland (northern modern Belgium) in the 16th century, but largely improved and popularized by Charles Townshend (Norfolk) in the 18th century with the goal to improve crops rotation/yields

- The improvement of the seed-drill machine by Jerhro Tull (Berkshire)

- The implementation of systematic selective breeding by Robert Bakewell (Leicestershire)

- The development of the Southdown sheep through selective breeding by John Ellman (East Sussex)

The progress was not only technological as British agriculture evolved on many topics with the creation of a nationwide market for agricultural products and improvements in communications/transports. All these improvements proved necessary to sustain the ongoing British industrial revolution. Like many other agricultural regions, Norfolk was affected too by the Great depression of British agriculture between 1873 and 1896, an event linked to the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 and an increase in food imports from abroad. Something we will discuss later on.

The agricultural landscape of the United Kingdom was transformed. Many things are now considered as being part of the past. We can mention the “foot-plough” in Scotland for example (rather than using a horse/oxen pulled plough, it was done by using a long stick called a “cas chrom”, something required because the soil is of poor quality and rocky in some parts of the Scotland) or several agricultural practices like the “run rigs” and “lazy beds”, which had left a distinctive mark in the agricultural landscape :

Food and traditions

Life in the countryside was transformed too. Several traditional celebrations were either forgotten over time, or far less practiced like Wassailing — a winter orchard-blessing custom — Lammas Day — feast of the first wheat harvest — but some of them survived till today. The Plough Monday dates back to the 15th century and is celebrated at the beginning of January. It symbolises the start of the agricultural year. It was common to drag a plough around and collect money. May Day is a very old festival associated with spring celebration. It’s well known for the custom of children dancing around a pole (called the “maypole”). Here are some pictures illustrating these two festivals :

Today, many agricultural shows are organised both for professionals and for the general public : The Royal Highland Show, The Royal Welsh Show, The Great Yorkshire Show… One celebration was also revived in the 1990s : the Apple Day to celebrate orchards, fruits and also apples of course. While not specially dedicated to British agriculture, we can mention several movies celebrated for the beauty of their British landscape :

- Akenfield by Peter Hall (1974) : telling the story of a small fictitious village in Suffolk (Akenfield) and the life of its inhabitants over several decades

- Levelling by Hope Dickson Leach (2016) : a social drama set in the Somerset, revolving around a familly struggling to keep afloat a farm

- Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Vinterberg (2015) : a romantic drama set in Dorset

- Withnail and I by Bruce Robinson (1987) : a comedy about two alcoholic and unemployed British men from Camdem Town who embark on a journey to Lake District (Cumbria)

- God’s Own Country by Francis Lee (2017) : a drama about a young sheep farmer in Yorkshire meeting a Romanian migrant worker, less known for its landscape but more for its representation of farmer life in the North of England

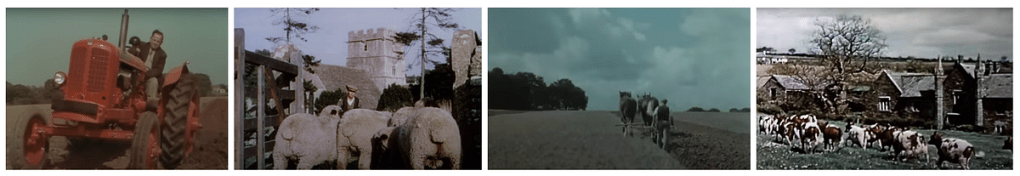

While discussing movies, we can discuss the documentaries produced in the 1930s-1960s to inform the public and promote British agriculture. They were generally done to be broadcast in cinemas like newsreel movies for example. Many of them are now available through British Pathe and BBC archives. Some of them are well known like “West of England” (1951), “The Harvest Shall Come (1940)” — filmed in Suffolk — and several episodes of the “Look at Life” (1959–1960) series about British agriculture — especially the agricultural west. While a bit anachronistics, most of them are useful to remember how daily life and agricultural works were in the past.

Here are two historical British agricultural movies — “West of England” (1951) and “English Harvest (1938) :

On the topic of traditional British agriculture, we can discuss food too. The fact that many French, me too, are sometimes (to say the least) a bit “puzzled”–setting apart the fish’n’chips–when looking at British food is more of a prejudice and a testimony of our complete ignorance of this part of British culture. While not exactly baked as in the United Kingdom, I have personally a great taste for pudding. A situation deeply ironic when you know that this country is home of so many well-known chefs (though they are well-known for cooking French cuisine for many of them) like Gordon James Ramsay, Marco Pierre White, Jamie Oliver… From my perspective, one British specialty that could reconcile many foreign people with British food are British pies; whether it’s filled with pork, beef, steak, and sometimes potatoes or even swedes. A product that is generally considered to have merged from Tudor times. Here are a few of them :

British cuisine developed over centuries in fact. The oldest British cookery book is “The Forme of Cury” (published around 1400). While the original is lost, the book survived through several copies. Another famous old manuscript is the “Utilis Coquinario”. But one of the most important of them could be the “Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book” which contains a lot of information (both culinary and historical) on British food during Elizabethan times. To add a final word on British food (and with no intent to lampoon British food) here are three dishes I choose both for their names and their importance in British culture; in the sense that their names are really unusual and could have a comical/“double-meaning” sense :

- “Spotted Dick” : the word “dick” is to understand in the sense of a “pudding” but over time, it became something of a joke — especially for foreigners — due to a change in the common language (“dick” being now associated with “penis”), and the resulting weird association between something obviously sexual now and a very traditional British dish

- “Toad in a Hole” : something comical given the fact that there is no hole neither toads in this dish

- “Stargazy Pie” : a traditional Cornish dish, very unusual for a non-British person and not well-known outside the United Kingdom; that could look absurd given the contrast between the whimsical name (“stargazy”) and the unusual aspect of the dish that includes one or several fishes with their eyes

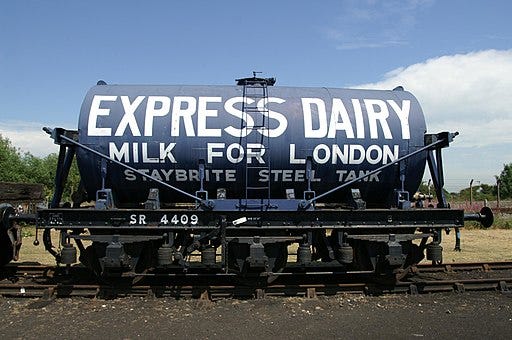

British agriculture is also well-known for its dairy products, especially milk. The dairy industry has been well established in the United Kingdom since the early times (along with livestock farming), but grew rapidly during the Industrial Revolution — especially with the discovery of pasteurization. The demand was so important that “rail milks” were created and were common sights on British railways :

The “rail milks” use peaked during the 1930s-1960s when it was replaced by road transport through the 1980s. At one point, especially after WWI, the production was so huge that quotas were required to avoid a collapse of the market. The “Milk Marketing Board” was created in 1932 with the goal to assist the producers, monitor the market and to enforce single price over milk. The 1970s saw the height of “milkman” services in the United Kingdom, before a progressive decline with the introduction of plastic bottles and milk in supermarkets. Because of political changes, the “Milk Marketing Board” was increasingly criticized and finally abolished by John Major in 1994. It meant that the milk producers had to struggle with non-regulated prices and to deal with supermarkets. Today, like in many other countries, milk producers are struggling with low prices and changing habits. While struggling, milk production reached 12 billion liters in 2023.

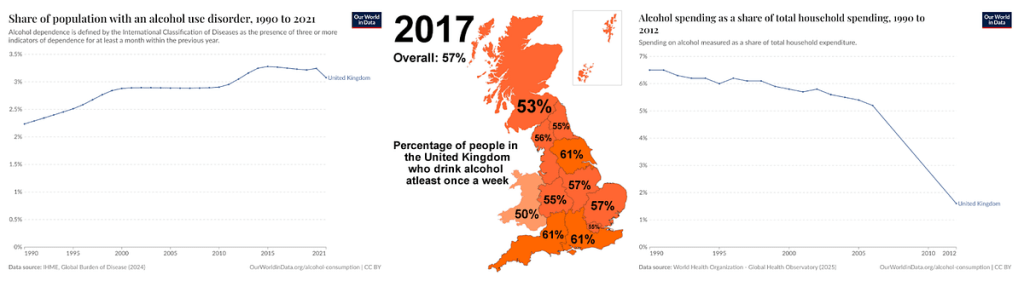

Beers, ciders and wines are also an important part of British culture. Alcohol production has been done in the United Kingdom since at least the Roman Period. Due to climatic constraints, the growing of wine is essentially limited to Southern England (Essex, Sussex, Kent…), and is relatively limited compared to beers and ciders. The history of beer in the United Kingdom is interesting because it’s partly tied to the religious history of the country. Traditionally, beers were made by religious orders across the country in the Middle Ages (especially monasteries). In 1527, Henry VIII was willing to divorce and requested the annulment of his marriage to the Pope Clement VII . Following the rebuttal of the Pope, Henry VIII decided to remove papal authority over England by enacting the English Reformation (inspired by Protestantism, while retaining some catholic straits especially during religious services). One of the consequences was the “Suppression of Religious Houses Act” in 1535 leading to the closures of several monasteries. With the loss of these production units, the beer sector was one of the first to witness the development of incorporated companies like the “Shepherd Neame Brewery” (one of the oldest brewing companies in the UK) in 1698.

Despite a decline in consumption in recent years, it remains high compared to other countries, with the arrival of new beers on the British market (like the IPA) and new trends like cider consumption “revival”. This is actually a major public health concern in the United Kingdom : rising alcohol-related disorders, alcohol-induced mortality, alcohol consumption by youth…

Saving rural heritage

Several public bodies and associations were created over time to preserve the agricultural and natural heritage of the United Kingdom; and more especially in England. One of the earliest examples was the “Council for the Preservation of Rural England” (known today as the “CPRE, The countryside charity”). It was created in 1926 by Patrick Abercombrie, and was one of the first associations in England to campaign against urban sprawling, rural areas preservation and national parks creation. Two public bodies were created respectively in 1984 and 2006 to preserve/inventory the rural areas (historical buildings, landscapes…) : Historic England (known as English Heritage previously) and Natural England. We can mention the National Trust too founded in 1895, with the goal to preserve valuable buildings and landscape. The trust was given statutory power in 1907 with the “National Trust Act”.

Less-known outside the United Kingdom is the story of nature preservation. In the 1800s, with growing tourism in some parts of the country, many people enjoyed discovering the moorland of Kinder Scout (Derbyshire, England). It led to many legal battles with the landowners who made everything possible to prevent people from walking in the area. The matter became more and more difficult to handle in the 1930s as more and more people in the United Kingdom were willing to discover nature and escape the difficult conditions in some cities. It led ultimately to what is called now the “Mass trespass of Kinder Scout” in 1932 when hundreds of people decided to walk within the moorland. But that’s only decades later that the right to roam in nature was instituted, in a limited way, with the “Countryside and Rights of Way Act” (2000). Another subject was the protection of woodland, something that led in 1996 to the “Newbury bypass protest”. While the Newbury bypass was built, the cost of handling the protest in this case led to the abandonment of multiple projects across the country. On the topic of preservation, here are some examples of key agricultural buildings of historical value still preserved today across the United Kingdom :

Several British authors (in the past and today too) have produced extensive works on the British countryside. One of the most known, and also controversial, was Henry Williamson (1895–1977) and his famous book « Tarka the Otter » (a story about an otter and the opportunity for the author to explore the « Two Rivers » region in Devon County, turned into a movie in 1979), and his work in several volumes known as « A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight » (a collection of novels). During the inter-war period, he became close to Oswald Mosley and his fascist organization (The British Union of Fascists), facing scrutiny by British authorities at the time. Another famous author is Adrian Bell (1901–1980), known for being the first compiler of the « crossword » section of the Times, and more importantly, a rural journalist and a farmer.

More recently, we can mention James Rebanks (born in 1974) who gained notoriety with his book “The Shepherd’s Life : A Tale of the Lake District” published in 2015. Melissa Harrison (born in 1975) is another interesting figure. She writes books about the wildlife and countryside. Her book “The Stubborn Light of Things” recounts her move from London to rural Suffolk. And to conclude, we can speak of H. J. Massingham (1888–1952) Well-known for his numerous works describing the Cotswolds (an important and touristic rural area in the South-West of England).

To conclude on this section regarding British agricultural memories, we can mention the website sussexpostcard dot info. It’s a public archive of several postcards taken in Sussex county, especially in the early 1900s. While all the pictures were taken in Sussex, it’s a great opportunity to discover past pictures of British agricultural life. One example :

Dig for Victory

A less known story regarding the history of the British agricultural system is the allotments system. With the progressive disappearance of the commons, it was important to find a way to allow people to feed themselves both in the countryside but also in growing cities. This was done through the “Allotments and Cottage Gardens Compensation for Crops Act” in 1887. It was necessary in several key urban areas overpopulated and facing huge social challenges among the working classes. The first act proved unsuccessful to implement and faced resistance from local authorities, and was followed by several other acts in 1908 and 1950. These allotments were critical during World War II with the “Dig for Victory” campaign in the United Kingdom to improve food availability for the British people.

The continuity of the British agricultural geography

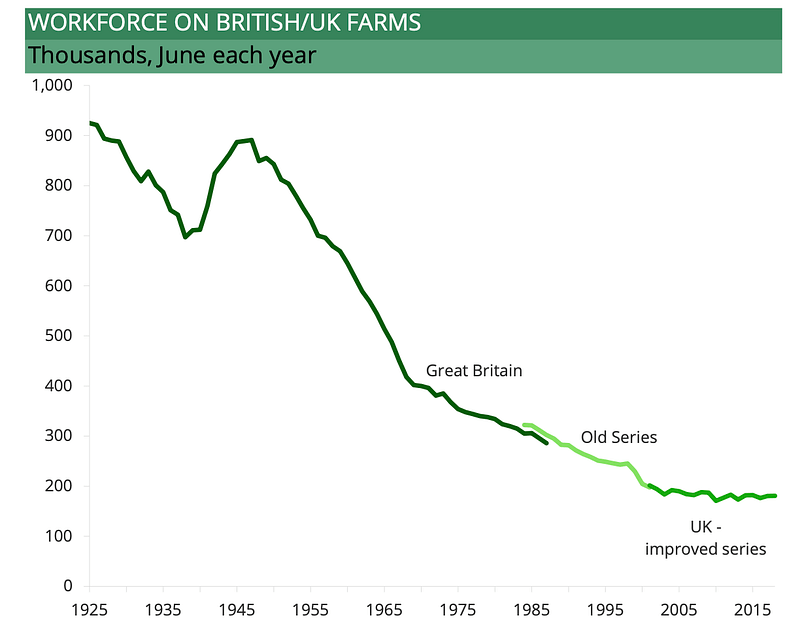

The documentary “Norfolk Past” began in the 1900s with several scenes in the countryside and the coastal cities of the country. A very rural country, like many in the United Kingdom and many European countries at this time. Like many agricultural regions of the United Kingdom, many challenges were ahead : the exodus from the countryside to industrial towns, the lack of workforce, the progressive mechanization of the agricultural landscape (meaning fewer job opportunities for many workers) and the impact of global trade since the abolition of Corn Laws.

Machinery

Regarding mechanization, the United Kingdom was ahead because the country was considered to have invented the Industrial Revolution. Several companies were manufacturing steam-powered tractors, traction engines and ploughing machines in the United Kingdom (and many of them in Norfolk) : Ransomes, Sims and Jefferies Limited (Norfolk); Charles Burrell & Sons (Norfolk); Aveling and Porter (Kent); Wallis & Steevens (Hampshire); John Fowler & Co. (West Yorkshire)… Here are some pictures of these antique vehicles :

Since the 1950s-1960s, many efforts have been made to restore/save these old machines in the United Kingdom. Steam fairs have been organised since the 1960s by hobbyists to exhibit these old machines. While popular, many of these events faced rising costs and were progressively cancelled. Like the famous Great Dorset Steam Fair (unfortunately stopped in 2022) or the Grand Henham Steam Rally (liquidated in 2020). Of course, over the decades, steampowered machines have been replaced like everywhere by tractors, sprayers, combine and sugar beet harvesters…

Agricultural patterns

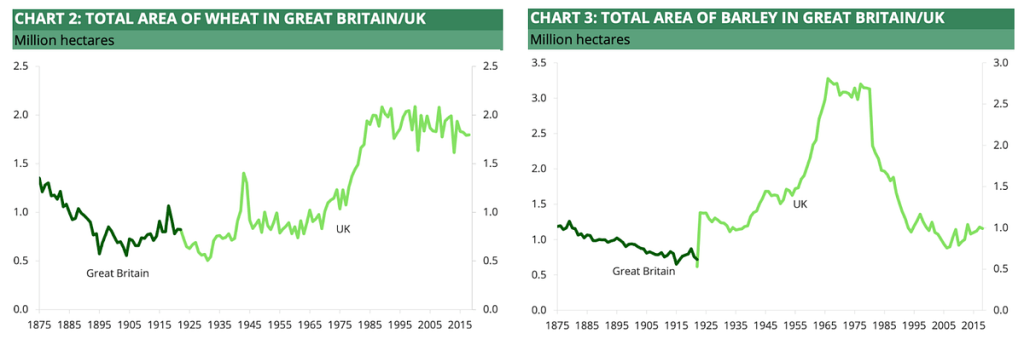

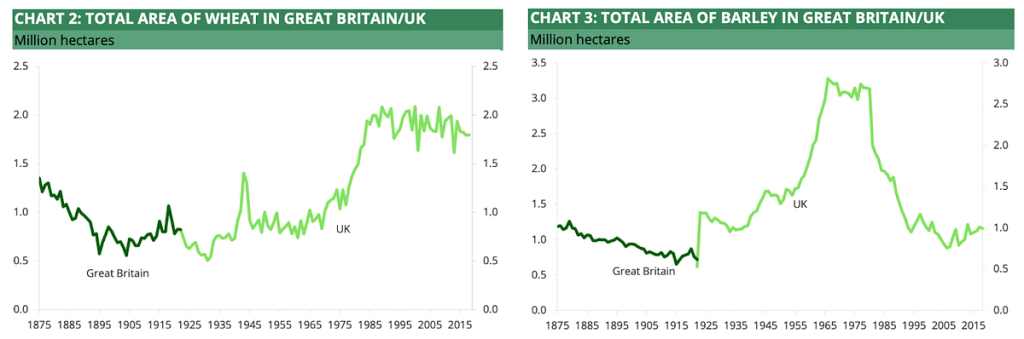

These agricultural statistics from the House of Commons Library (Number 3339, 25 June 2019) are telling with the clear collapse of the wheat and barley surfaces from late 1800s to early 1900s :

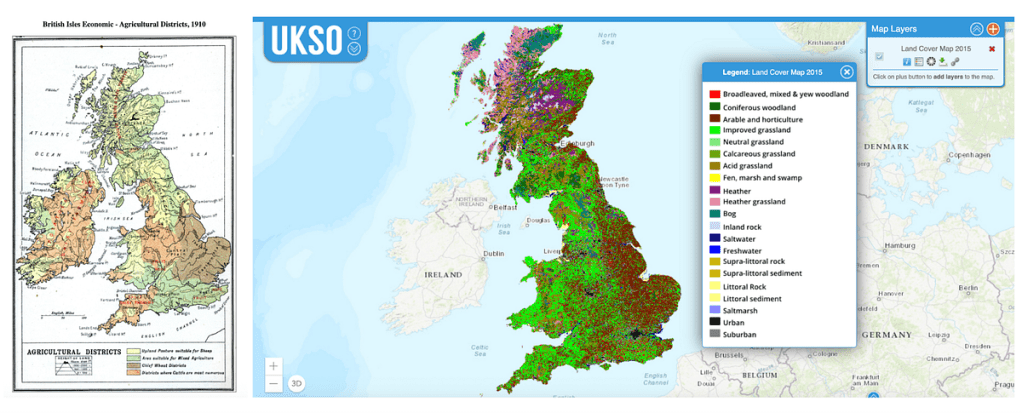

At this point, the country was already importing a lot of its food. Something that should make us aware of the British agricultural landscape : the critical and historical value of the East of England. Something deeply ingrained in the geographic history of the country with two maps of the agricultural landscape of the United Kingdom between 100 years :

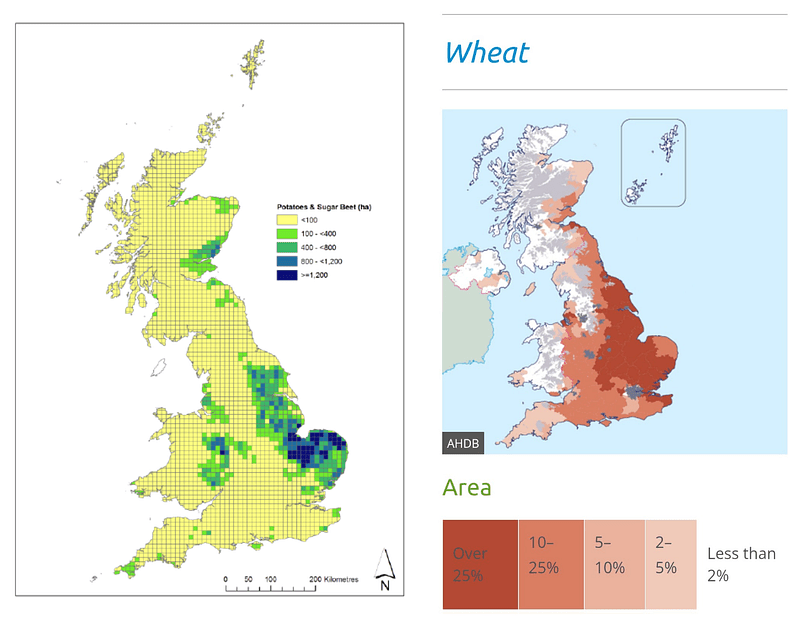

And also two maps regarding where two major agricultural crops are planted and/or harvested (wheat and potatoes) :

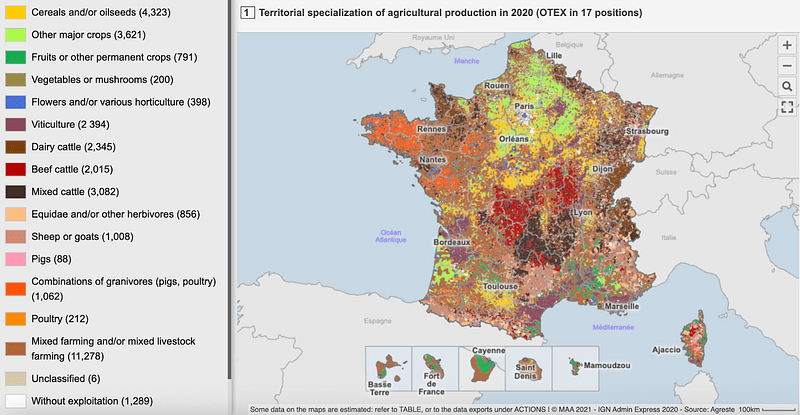

Something interesting to understand the geographic constraints of the British agricultural system is a short comparison with the French agricultural landscape. Here is a map made by the Agreste (The statistical service of the Ministry of Agriculture in France) on this topic regarding agricultural lands :

While many of the “crop-lands” are concentrated in the North (especially around Paris and Ile-de France), the fact remains that the geography of the arable lands in France is a bit more dispersed in France than in the United Kingdom. Several pockets of “crop-lands” are visible near Bordeaux and Toulouse for example (in the South-West), near Lyon and the East of the country (especially the Alsace region). The clear-cut is less obvious than in the United Kingdom. Interesting too are these statistics about the arable lands (those generally dedicated to crops : cereals, potatoes, barley, vegetables…) : with nearly the same population in both countries (circa 68 million people), the United Kingdom got only 6 million hectares of arable lands, against 18 million hectares in France; meaning that the United Kingdom agricultural system faces massive challenges inherent to its geography to feed its people.

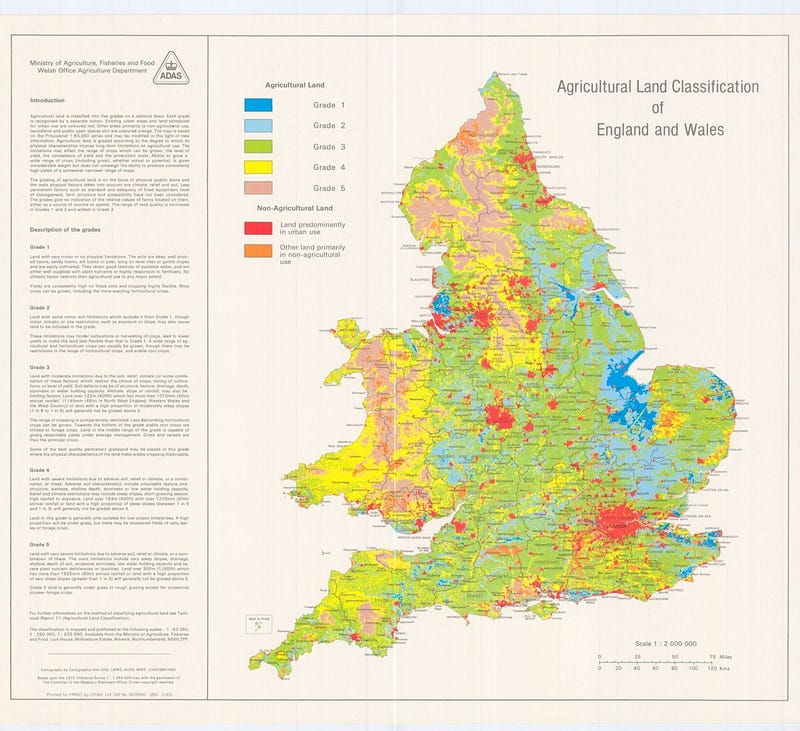

As you can see, the East of the United Kingdom concentrates most of the arable lands suited for crops farming (wheat, barley, potatoes, vegetables…) while the West of the country is largely suited for pastures or mixed-farming. Something closely tied to the nature of the soil in the eastern regions of the country. Something nicely illustrated by this 1985 map :

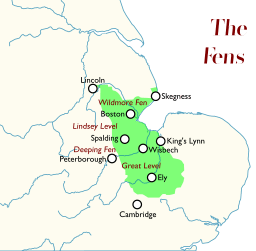

In blue, the most valuable lands of the country. As you can see, most of them are in the East from North Yorkshire to Kent, with some important areas in Hereford and also Lancashire north of Liverpool. The agricultural development of the East — setting apart the natural value of the soil — is also something that was probably made possible by the “conquest” of the Fens region. The region is located here :

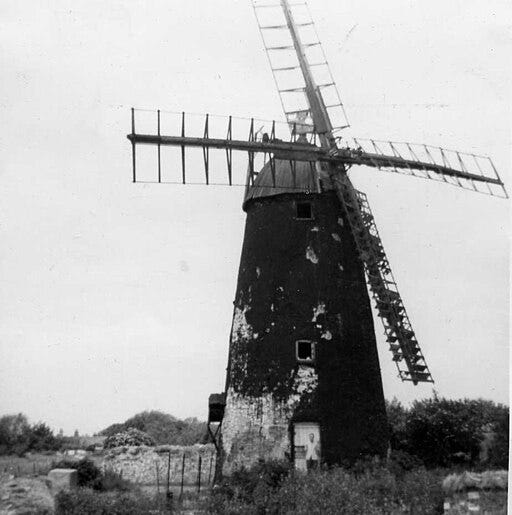

Historically, the area was a marsh. The Romans attempted in a very limited way to drain the area, but it didn’t change the agricultural/physical landscape of the area. Efforts were pursued in the 1600s with wind powered draining pumps. But the efforts proved unsuccessful in several areas, with soil lowering and re-flooding of past drained areas. It remains largely a pastoral area for this reason.

But most of the work was accomplished between the 1800s-1900s. It was made possible by the advent of steam powered draining pumps. An example of a past steam engines used to drain the area :

Specialization

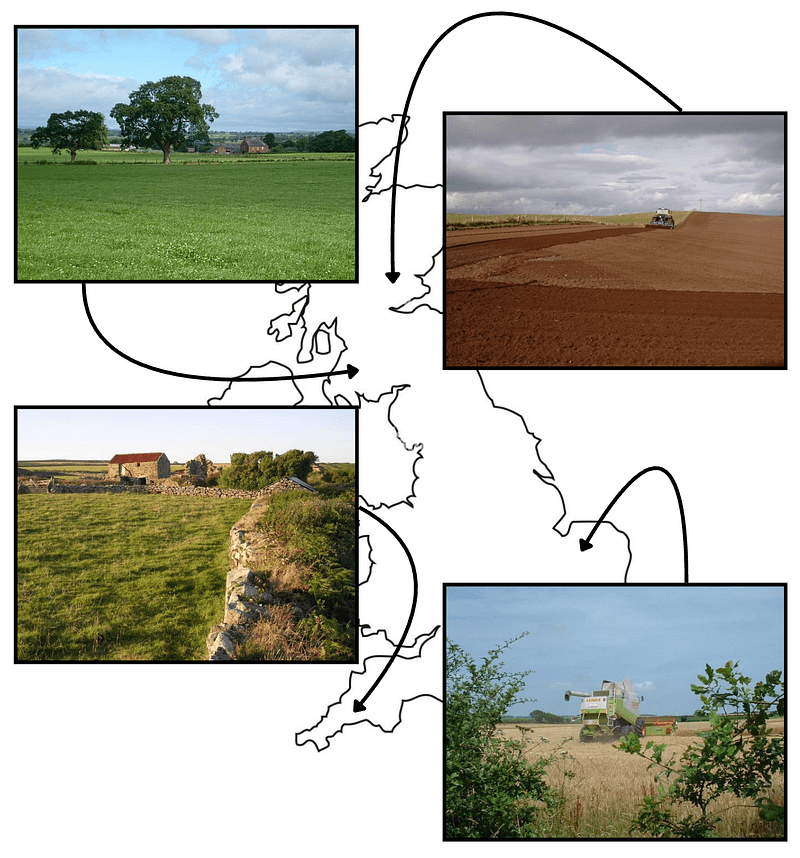

Following the success of the operation, the agricultural landscape of the area was totally transformed. Crops have progressively replaced pastures over this area, and livestock farming is now only a fraction of the agricultural system of the Fens. This agricultural specialisation is now deeply entrenched in the British agricultural system. As illustrated by this collage :

These landscapes reflect both the historical (and continuous) agricultural practices in several British regions, and also the natural shift toward mechanized crops in the flat lands in the East of the country (wheat, barley, potatoes, sugar beet…) and the pastoral continuity in the West. It’s also interesting to remind the reader that British agriculture is not limited to cereals, livestock and dairy. Wines and even strawberries (especially in Scotland) are also produced in Britain. The wine industry is interesting because it nearly vanished with the onset of WWI. Wine production was introduced by Romans in England. In the Middle Ages and onward, England was importing a lot of wines from France, till restrictions on imports were put in place in the 1700s. Wine production ceased for several decades before and after WWI until the late 1930s. Wine production resumed modestly in the 1960s, and expanded through the 1990s-2000s. One region to perfectly illustrate this reality is Kent, nicknamed the “Garden of England” with all its small orchards. Here is another collage to illustrate this reality :

Horticulture

Even if not directly tied to agriculture (crops or livestock), the United Kingdom is well known for its garden. Something tied to a less-known economic sector : horticulture. The United Kingdom had a long history, dating back to the Victorian era, with greenhouses (or glasshouses). While the British climate is not made to grow exotic or “fragile” flowers and plants, the fact is that during the Victorian era, the British empire was at its peak (India, Australia, South Africa….). It was fashionable to bring back products from these countries, leading in turn to the need to build proper structure to protect and grow them. Many large and expensive glasshouses were built across the United Kingdom, what is called in the UK a “palm house”. A large glass structure designed especially for tropical plants. Here a few notable examples :

Yields improvements and agricultural struggles

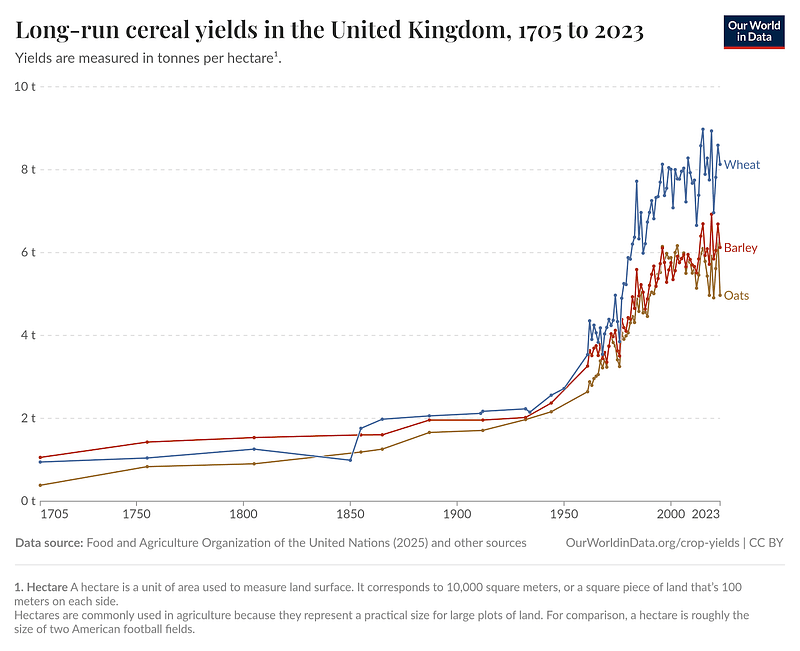

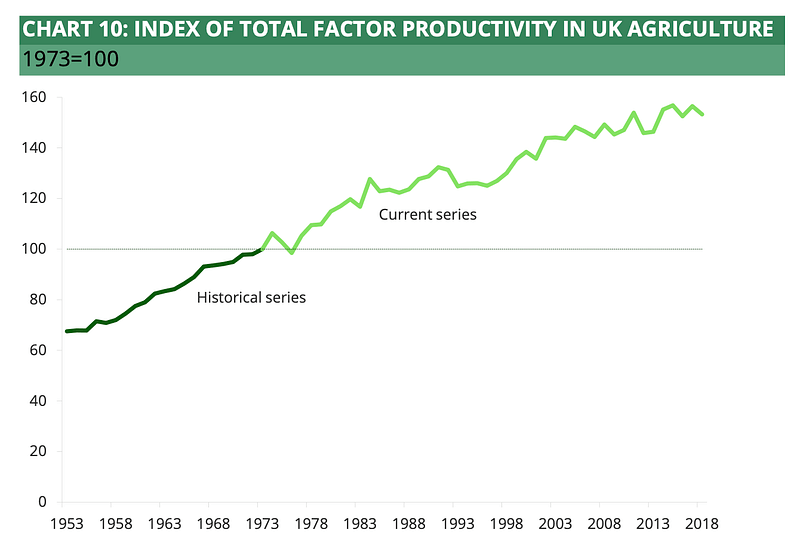

With improvements in the 18th century, enclosure and innovations, agricultural yields steadily improved over the centuries and then skyrocketed from the 1950s up to today as illustrated here :

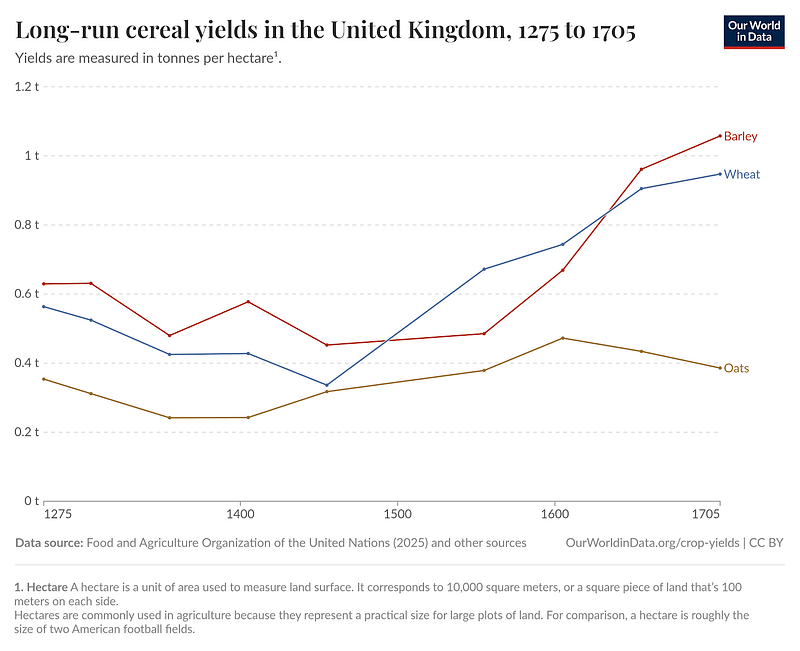

Something impressive when compared with early recorded yields during the Middle Ages and later on in the United Kingdom :

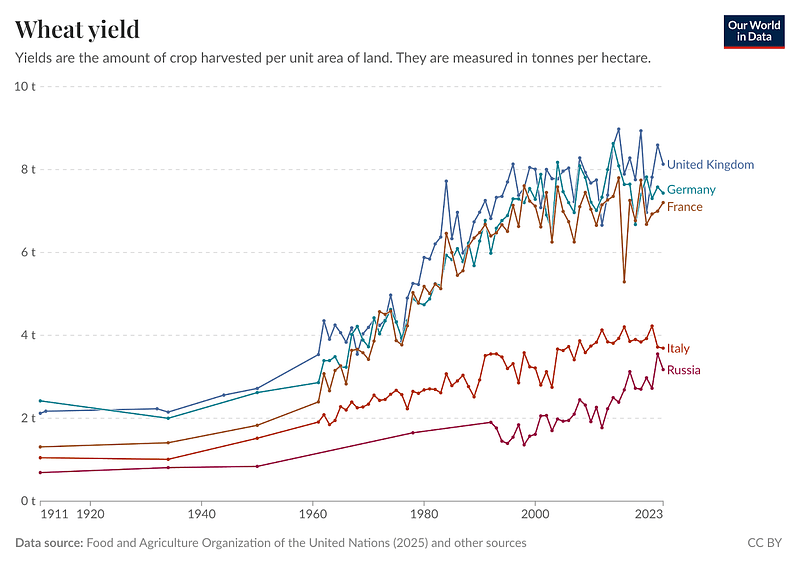

When compared historically with several others european countries like France, Germany, Spain or Italy, the country appears to have been always ahead of the continent regarding cereals yields :

But while the agricultural system thrived in some manner, the growth of the population and the rise of industrialization led to a shortage of labor and several agricultural depressions in the country throughout the 1800s.

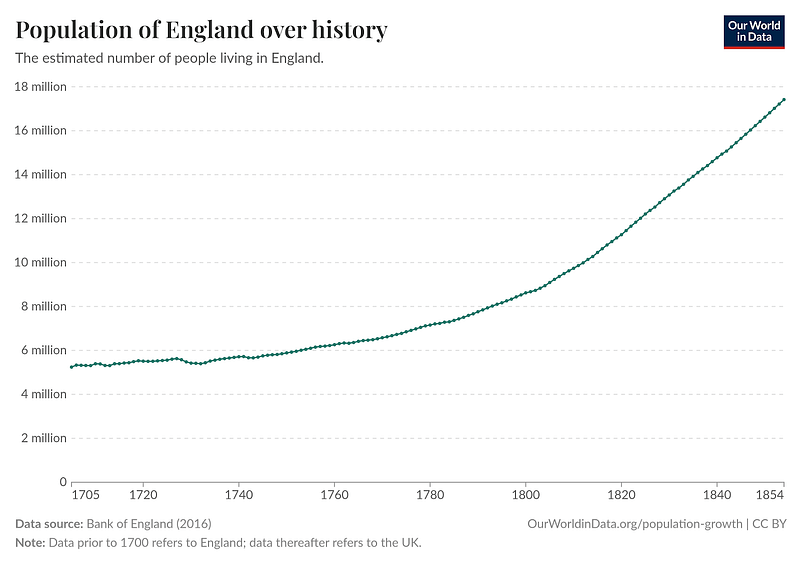

At several points in British history, the country was heavily dependent on imports to feed its population. That’s still a major political topic in the United Kingdom since the 1850s (year of the Corn Laws repeal) : should and could the country be food-import free ? To understand, here is the demographic curve of the England from the 1700s to the mid 1800s :

In this context of an exploding demographic curve, the British agricultural system faced several depressions. The first major crisis between 1815 to 1836. This crisis led to the introduction of the Corn Laws provisions to protect the interest of the British farmlands with several tariff measures on grain imports in 1815. The next year, 1816, was marked by the major climatic disruption called “Year without summer” which caused several food shortages after major crops failure throughout the United Kingdom and Europe.

Corn Laws repealed

The disastrous first two years of the Great Famine in Ireland (1845 and 1846) with calls to import food to feed people, and the possible political shift in favor of more global competition, led to the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. The next crisis called the “Great depression of British agriculture” occurred between 1873 and 1896. The country faced several bad harvests during the early 1870s. With no tariff barriers on grain imports, the country was quickly flooded by imported wheat, but also meat, butter and cheese. Prices plummeted and many people left the agricultural sector. The country had no choice but to import more foodstuff from abroad, creating a self reinforcing loop in the agricultural system : more competition, falling prices, less labor force, less lands, less farms…

To understand this, we should also understand that the United Kingdom was in complete transformation between the 1800s-1900s with urbanisation and industrialization. An impressive shift of people and power is being made from rural areas to thriving mining regions and industrial towns as illustrated by this map :

London of course, but more especially northern regions. Especially Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds… This shift was difficult to sustain for the British agricultural system of the time.

Tenure system

Setting apart the population growth, the British agricultural system was likely hampered too by the slowly evolving land tenure system where the agricultural lands were properties of large landlords and used by tenant farmers. Several systems existed in the United Kingdom. The main were or are still existing in the United Kingdom :

- Tenant at Will : the farmer rents the land without long term contract to a landowner

- Leasehold Tenure : the farmer is granted a lease for several years (3, 7…) with several goals for the farmer

- Copyhold (until the 19th century) : a system where the relationships between the landlords and the tenants, and also the tenants’ rights, were written in a register and the tenant got a copy of the record; the system was abolished by several Copyholds acts between 1841 and 1894

- Freehold : the farmer is the owner of its own land (the status of landowners)

This situation led to the “Agricultural Holdings Acts” from 1875 and onwards to regulate/improve agricultural tenancies in the United Kingdom.

Women’s Land Army

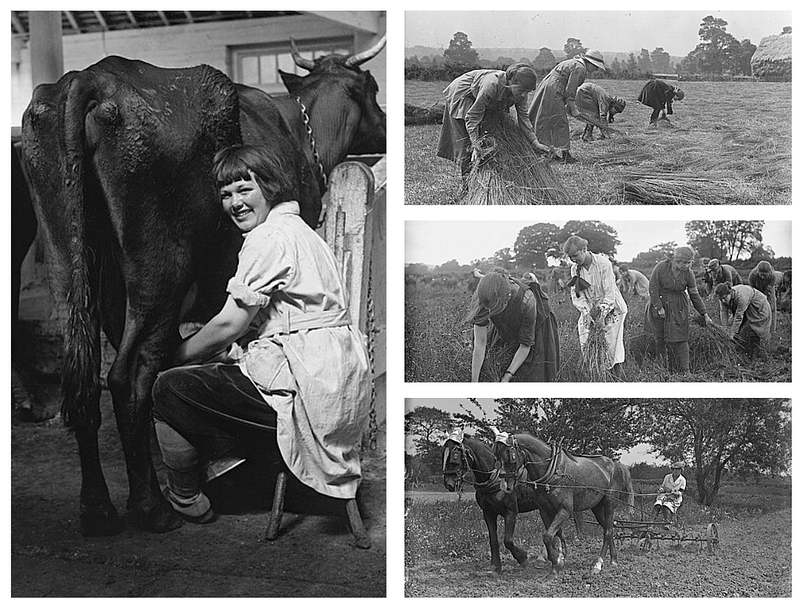

The British agricultural system started to bounce back first with the First World War and more importantly, with the Second World War when for several years, the agricultural system was put under government control for urgent redevelopment given the war in Europe, lack of strong agricultural, starvation risks… It was during WW1 and WW2 that the United Kingdom mobilized a lot of people, notably women with the Women’s Land Army (called sometimes Land Girls) and also soldiers. A few pictures from the book The Women’s Land Army in Britain, 1915–1918 by Horace Nicholls :

And some pictures of soldiers assisting British farmers in the 1940s during harvests (Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) :

Agriculture Act 1947

Something achieved also with the “Agriculture Act 1947” after the war : guaranteed prices, improvement and investment in agricultural machinery… What was also important was the introduction of several provisions regarding the tenure system to improve farmers’ security. European integration (at least before Brexit) was also an important factor for improvement of the British agricultural system. As nearly all agricultural systems across Europe, the United Kingdom made no exception and productivity improved while the labor force diminished.

One of the key issues arising through the 1970s and 1980s, like in many countries, was the increase in surplus for several products and falling prices. Quotas were put in place for several products like milk. While a necessity to feed the British, the British agricultural system barely accounts for more than 1% of the total workforce in the country, and perhaps 1% of the Gross Domestic Product.

East of England

Like in many countries, agriculture is now something of a “shadow” for many people. Something obviously required for people to live in this country, but something sometimes a bit neglected given its reduced visible weight in public and political discussions (1% of the total workforce in the country, and perhaps 1% of the Gross Domestic Product). If we go back to the East of England, and despite all the changes having occurred politically, socially and economically in this country over decades and centuries, here is how important it is still now for cereals and agricultural production :

Something that shows few differences with the past, at least since the early 1900s. A bit like if both the soil, farmers (even if diminished) and crops were telling us a story of persistence; whatever occurred around them. These 2023 statistics from the DEFRA regarding farming types in the three most productive regions regarding cereals (East Midlands, East of England and South East) are telling :

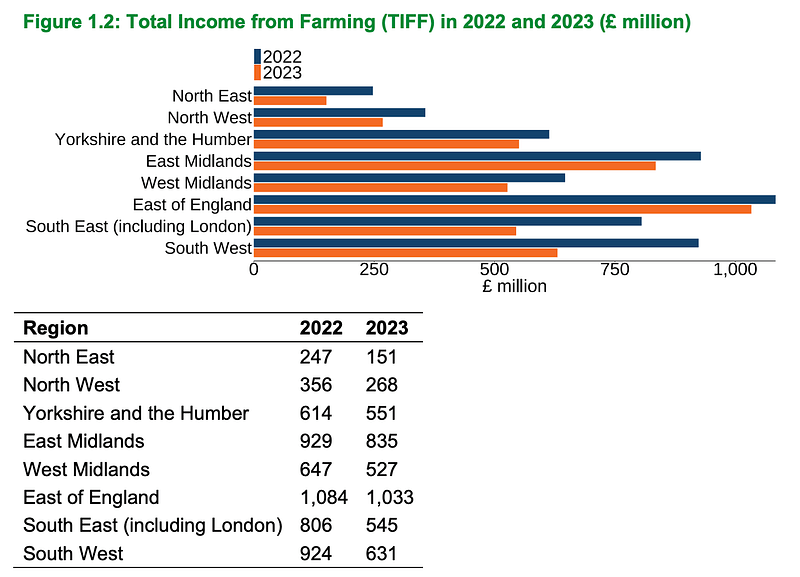

These statistics by DEFRA too show clearly how the East of England outpasses all agricultural regions regarding revenues, especially for crops :

This simple persistence of the British agricultural system, especially geographically, is interesting for a country where so many British politicians don’t consider food security as a vital national topic anymore. One dangerous argument heard in many countries — something not specific to the United Kingdom — is the political objective to reach cheap food and the obsession — from my outsider and non-British point of view — with reliance on international trade. Something that, from my perspective, has also a lot to do with how people live and make decisions now, rather than mere political opinion. The fact is that thriving political and economical centers in the United Kingdom are in cities like London, and not in rural counties.

Of course, it doesn’t mean that sometimes, people aren’t forced to step back when some boundaries are crossed on this topic. It was the case when the aide of the former PM (Prime Minister) Tony Blair, John McTernan said in November 2014 that agriculture was not a vital industry in the United Kingdom. A declaration that led to backlash and even the PM distancing himself from such statements.

In a more light-hearted manner, we can mention the suggestion by the Environment Secretary Therese Coffey in 2023 to temporarily replace fruits/vegetables by turnips, to circumvent shortages in supermarkets. Something met with humor and skepticism by many British people, but something interesting from my perspective, as it brings the topic of seasonality regarding food production and consumption in the United Kingdom.

What if the Cold War had met with East Anglia ?

The fact that many politicians in the United Kingdom show such a profound disinterest for agriculture and food security is somewhat funny — in some way — when you look back at the 1980s when there were several heated debates and protests over UK involvement in NATO. The proof that food security is far from being a whim, and that the most critical agricultural region of the United Kingdom was — and is — not only vulnerable to agricultural prices shocks or poor policy choices.

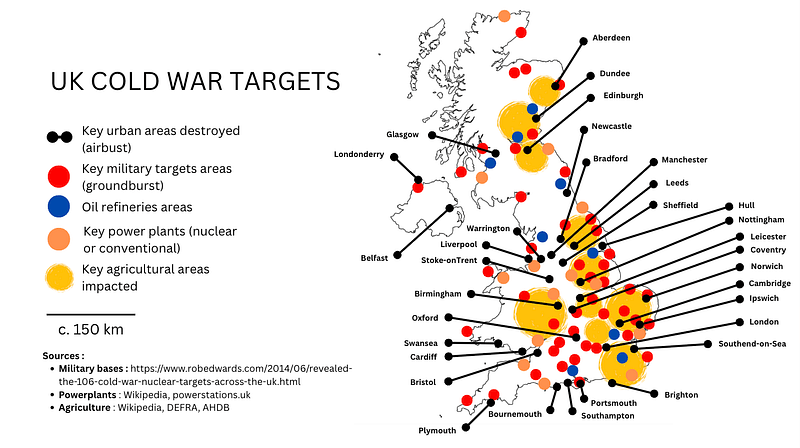

In the 1980s, the East of the country (from Kent to North Yorkshire) was home of many military bases (NATO or RAF). Several exercises were conducted by the country in the 1980s, especially Square Leg and Hard Rock. What could be seen from the plot maps is that several agricultural areas could have been seriously impacted in case of a full-scale nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union during the Cold War as illustrated with this map :

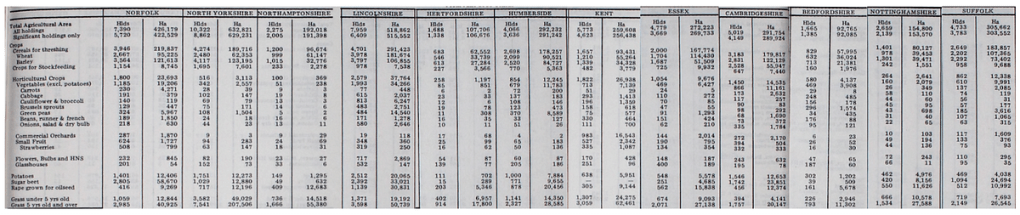

Something barely discussed, surprisingly, in public discussions in the UK at the time; but something that would have definitively mattered if such a disaster should have occurred : especially if importing was not possible for a long time. Concerning too when the United Kingdom was dependent for so many crops on the Eastern counties as depicted by this statistics of 1983 :

All these counties, located in the Eastern part of the countries from Kent to North Yorkshire, accounted for more than 50% of cereals (especially wheat) and potatoes, 70% of vegetables and nearly all sugar beets. The fact that the main concerns in public debate at this time — especially after the release of the BBC war-drama Threads in 1984 — in the United Kingdom were more about radiation, civil defense efficiency and disagreement with Thatcher policy is telling in some way. This potential fictional disaster reminds us of how valuable and vulnerable this part of the country is.

Concerns, future and revitalisation of British agriculture

British agriculture, international competition and laissez-faire

The value of the Eastern agricultural counties is interesting within the British political context because agriculture is recurrently a heated topic in public debate (as it was during the Brexit campaign). Since the Corn Laws repeal in 1846, many commenters believe that “free-trade” is since an important part of British culture. At the time of Corn Laws repeal, it was sometimes interpreted as a victory by the “industrial” country (especially the midlands where coal mining and industry were thriving) against the “rural” one. The fact remains that within British society, the common agreement over what is called in French “laissez-faire” and economic competition is not contested.

Even after the social struggles that occurred during the Thatcher era in the 1980s, the fact remains that British society has never expressed the willingness to return to a protectionist system, whether for agriculture, industry or services. Something important too is the fact that the United Kingdom had an extensive empire covering nearly all continents (Australia, New Zealand, India, Canada, South Africa…) for centuries. Massive investments were put in these countries/dominions. While British agriculture was not impacted for a long time after the Corn Laws repeal, it faced a boomerang effect in the 1800s when these new countries started to export a lot of food to the United Kingdom. Something that was detrimental to British agriculture, with a collapse in terms of farm figures, but also wheat and barley production. But something that should not be understood as “foodstuff-flooding” from foreign countries : these were British countries at the time too, and it would have made no sense — especially for a country where the laissez-faire was at the heart of economic philosophy — to protect the “metropolitan” market.

But with the collapse of the British Empire after the Second World War, and the collapse of coal mining and industry in the United Kingdom in the 1980s; should we understand that the British agricultural system made a comeback ? Not really. As shown by these statistics, the agricultural system was (and is) clearly redeveloped (especially for major crops like cereals) after decades of struggle :

But the fact remains that the British agricultural system is still struggling in a way or another, with many challenges ahead. The global agricultural workforce in the United Kingdom is still collapsing — like in many countries in fact — as shown here :

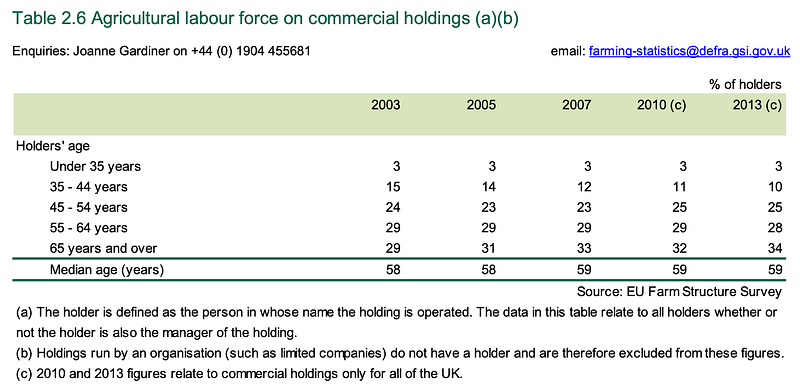

And also, while not specific to the United Kingdom, the average age of farm holders is also concerning with fewer and fewer young people working in the agriculture sector. Something we can explain by low prices at the farmgate and difficulties for young people to establish themselves in the sector :

British Livestock

While discussing earlier the reasons for the enclosure, especially pasture development for wool production, the fact is that today the livestock farmers are unfortunately the most precarious people in the British agricultural system. The British livestock farmers faced several crises. The first being the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) in the 1980s and 1990s. The second being the foot-and-mouth disease crisis in 2001. Like in many other European countries, milk producers faced plummeting prices despite quotas. In several livestock farming areas, like the Peak District National Park, many farmers have to rely on the Less Favoured Areas subsided to make both ends, and feed themselves and their family. A fact illustrated by these DEFRA agricultural revenues statistics for the England regions :

The key three thriving regions in 2023 were the East of England (majority crops farming), East Midlands (major crops farming) and South West (majority livestock farming). All regions behind them –while smaller by size– are either mixed-farming areas (crops and livestock) or majorly livestock farming areas. The success of the South West region can be explained by several factors : long history of livestock farming, tourism, better soils compared to other livestock farming regions (Wales, Scotland…) allowing for diversification, less dependency on EU agricultural subsidies… For Northern Ireland, the situation is rendered difficult by several past and actual political issues like the disagreements over the border with the Republic of Ireland.

To offer a few words regarding British livestock (because the essay is mainly about crops), and while this sector is struggling, this is still an essential part of British agricultural identity. There were a bit more than 9 million cattle in 2024, nearly 5 million pigs, 31 million sheep and 176 million fowls. The United Kingdom is well known for some of its species. Here are some of them :

Coastal erosion and climate change : threat to the East ?

Less known to the general public but extremely concerning : coastal erosion in the East of England. Norfolk and Suffolk are one of the most impacted regions by the issue, with a rate of to 2 meters per year lost to the sea for Norfolk. Threatened too is the Fens region — nicknamed sometimes as the “breadbaskets” of the country — where 50% of Grade 1 soils are located in the United Kingdom. Several challenges are ahead with both the threat of flooding due to sea level rising and also the risk of water shortage — critical for irrigation — due to drier summers — a major issue as this region is already one the drier of the United Kingdom. All these issues are critical as the country is unable to displace or replace these valuable agricultural lands. Several plans are underway to assist the region in face of upcoming ecological challenges like Fens2100+.

Some reasons for optimism ?

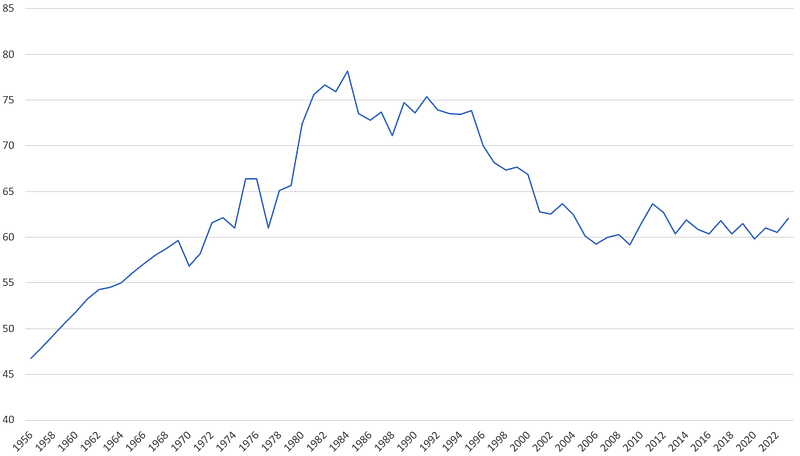

Regarding food production the fact is that the British agricultural system faces massive changes in consumer habits too. Many people — whether in the United Kingdom or elsewhere — want non-seasonal products in their store. More problematic than food self-sufficiency is also the concerns for farmers regarding how to adapt to changing habits. While concerning, the fact remains that the British agricultural system seems to be in far better shape than in the past. From 46% in 1956, the “self-sufficiency ratio” increased to 78% in 1984 — its historical peak — to fall again to 62% in 2023.

Self-sufficiency and the general public opinion

While marginal, some people in the United Kingdom are (or were) willing to open the debate on food self-sufficiency. The most famous of them being John Seymour, well known for his 1976 book “The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency”. More recently, Max Cotton (a radio broadcaster) spent one year on his self-sufficient farm in Somerset. Not necessarily related to agricultural self-sufficiency, but important regarding sustainable practices, we can mention Lady Eve Balfour too for her work on organic agriculture. While less “serious”, the British sitcom “The Good Life” (1975–1978) produced by the BBC, was one of the first TV shows to introduce the topic more broadly. Tom Good, bored of his job, decides (with his wife) to become self-sufficient and to grow his own garden in Surbiton (London Suburbs).

Despite all these challenges, British people regularly express their interest in agriculture and their farmers. A survey made by the National Farmers’ Union of England and Wales revealed that :

- 89% of the public feel it is important that Britain has a productive farming industry

- 85% of people support increasing self-sufficiency in UK food production

- 87% of people think it is important that trade deals ensure animal welfare standards are the same in countries we import food from as in the UK

The public interest is also noticeable with the ongoing show “Clarkson’s Farm” where we can follow Jeremy Clarkson (famous hoster of “Top Gear”) on his own farm in West Oxfordshire.

The topic of food self-sufficiency for any country reminds me of my own university dissertation when I was a student. The title of my dissertation was “La dynamique du « Made in France » est-elle porteuse pour les entrepreneurs ?” (or in English “Is the “Made in France” beneficial for entrepreneurs?”). The goal of this dissertation was to discuss the opportunity (and importance too) of self-sufficiency for France on several topics : industry, services and agriculture too.

The fact is that the United Kingdom government and other institutions are engaged, in some manner, in a process to develop and improve agricultural production. Many of those efforts remind me of what we see in France to promote products made in France, through several initiatives and also what is called “label d’origine géographique” (or “country of origin mark” in English). Many of them are privately operated, especially those not officials. The first one is the “Assured Food Standards” (known previously as “Red Tractor”) which sought to improve the share of British food in retails (livestock mainly with poultry, beef, lamb, dairy and also several crops). It issues several logos based on how much of the production is done in the UK. “Red Tractor” has operated in the United Kingdom for 25 years, and is still doing so. While praised for its actions, the company was criticized for several issues regarding animal welfare on some labelized farms. We can mention several initiatives like “Love British Food” to promote British food in several places like hospitals and schools. While not directly tied to British-made food, we can discuss the existence of “Landworkers’ Alliance” who promote sustainable practice and the defense of small farmers in the United Kingdom.

From my perspective, the issue in the United Kingdom is quite similar to what exists in France on this topic : the difficulty to reconcile globalized economic interests along with the urgent need for more local and sustainable systems.

To add a few words on Brexit consequences, the British agricultural system is facing numerous challenges threatening its goals for agricultural development. The most important is the difficulty to access the European market for its products since the United Kingdom left the European Union. Another major challenge is tied to the agricultural workforce, as the United Kingdom was employing many immigrant workers.

National Parks : another way to revive the British countryside ?

The fact too is that many efforts are done to revitalise declining agricultural areas, especially through tourism. We have mentioned the fairs earlier, and we can also mention the development of farm stays since the 1980s. The United Kingdom, like many other countries, have put a lot of effort into the development and preservation of its natural/agricultural landscape. The national parks were officially created with the “National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act” in 1949. Most of them were poor-quality agricultural uplands dedicated to pastures for some of them. Between 1951 and 1954, the following areas were designated as National Parks :

- Lake District (Cumbria, England)

- Peak District (Derbyshire, England)

- Dartmoor (Devon, England)

- Snowdonia (Wales)

- Pembrokeshire Coast (Wales)

- North York Moors (North Yorkshire, England)

- Yorkshire Dales (North Yorkshire, England)

- Exmoor (Somerset-Devon, England)

- Border Moors and Forests (Northumberland, England)

- Brecon Beacons (Wales).

In 1989, the Broads (Norfolk) were added to the list. The last places designated as National Parks were Loch Lomond and the Trossachs (Scotland) in 2002, the Cairngorms (Scotland) in 2003, New Forest (Hampshire, England) in 2005 and the Southern England Chalk Formation (East Sussex, England) in 2008. The National Parks are critical for many regions, as tourism creates revenues and job opportunities.

New Forest is interesting, regarding what I wrote earlier regarding the transformation of the British agricultural system between 1700s and 1800s, as it’s today the last remaining tracts of unenclosed pastures in South England. Setting aside the National Parks, there are also what is called Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). There are areas of major natural interest, but not considered as critical due to their small size or limited wildlife. Like in many countries with a national parks system, the British National Parks are entitled to manage several areas of development and planning in their respective areas. Interestingly, some of these areas were tied to past Royal Forests, like the Forest of Dean (Gloucestershire), New Forest discussed earlier or Hainault Forest (North of London outskirts).

Conclusions

While not British, I do have a strong interest in the British agricultural system, and still spent many hours reading/viewing things on the topic. Especially, because that’s something we barely know in France. A bit stereotypical, but the United Kingdom is generally more known in France for London, the Queen, some football teams, Olivier Twist and Billy Elliot, rather than for its agricultural landscape and culture. And I have an even more strong interest in the East of England. A region with such strong ties between history, culture and agriculture; still feeding the country for centuries, even if like in many places around the world, many farmers are struggling with market prices, changing habits. When looking at the history of the United Kingdom and its agricultural system, it’s interesting to see how these eastern regions were both important in early British history, home of several key agricultural innovations, and still are today for the British agricultural system despite all past (and new) challenges. Something we can illustrate with this map :

Four seeds in a row:

One for the mouse,

One for the crow,

One to rot,

And one to grow.

Laisser un commentaire